Lecture 3-The Social Brain and Interpersonal Subjectivity

“We are not thinking machines that feel; rather, we are feeling machines that think.” — Antonio Damasio

Objectives

- Explore how we understand and infer others’ inner experiences from a research perspective

- Learn about [some of] the brain regions involved in empathy, perspective-taking, and theory of mind

- Understand how social context shapes subjective experience and vice versa

- Discover tools that allow scientists to study shared mental states

- Reflect on what may lead to miscommunication

- Reflect on the bigger societal concerns when it comes to studying these things

The Social Brain: Making Sense of Others

Discussion Starter

- How do we know what someone else is thinking or feeling?

- Why do some people seem more attuned to others?

Key Questions:

- What are the brain mechanisms that let us “read” minds?

- Why do misunderstandings happen, even with people we know well?

- How do advancements in technology change how we think about these things?

-

Fantastic discussion on cross-species work in studying subjective processing (affect): The Transmitter Article

-

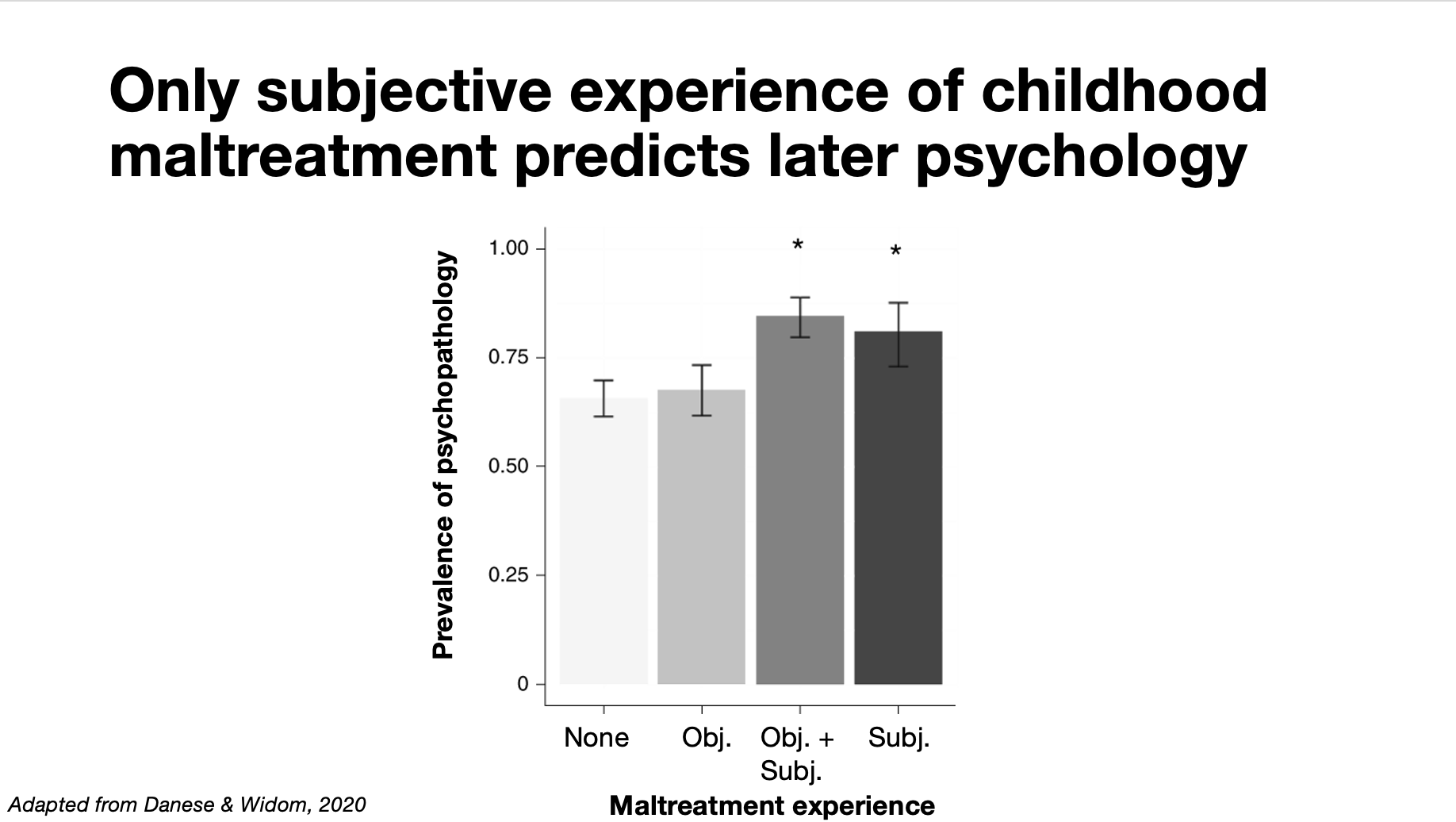

Fantastic demonstration of why subjective experience matters:

- Danese & Widom (2020)review

- original article

Section 1: Mentalizing and Theory of Mind

Core Concept: We build models of others’ minds

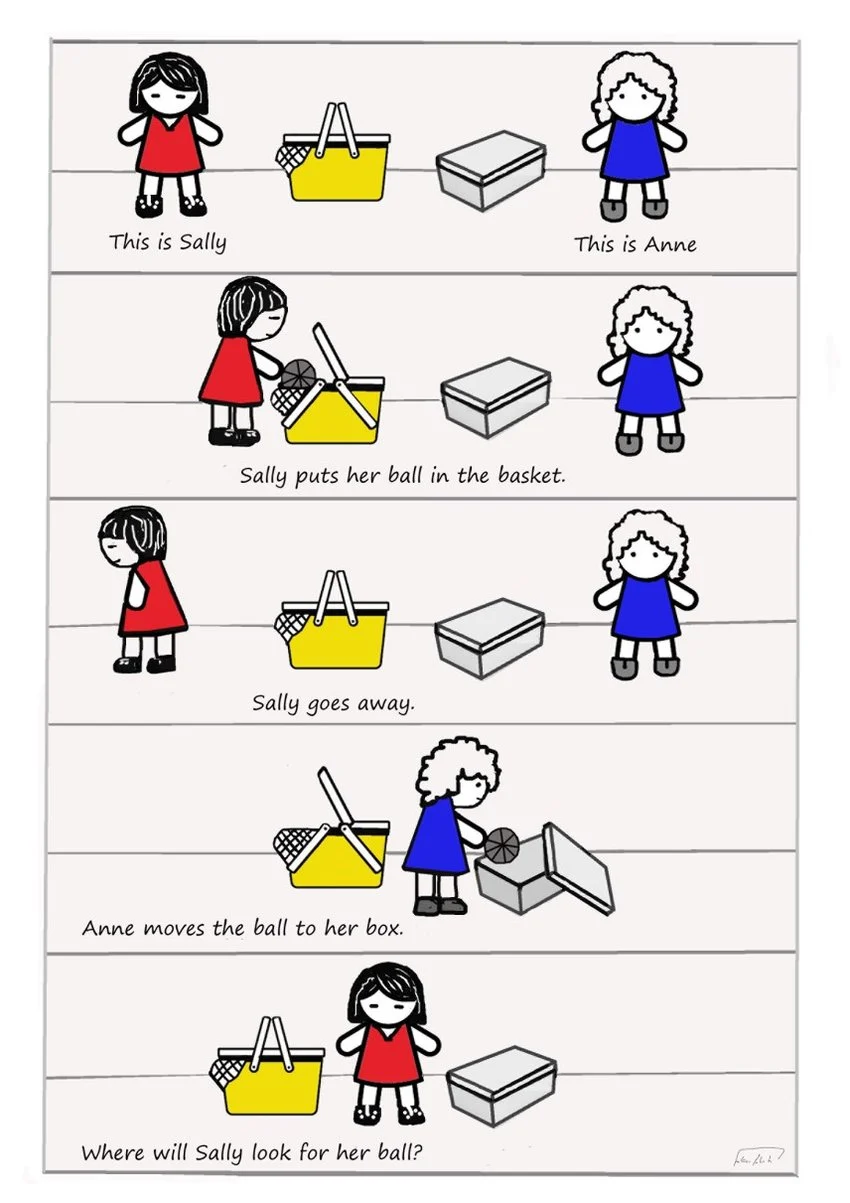

- Theory of Mind (ToM): the ability to attribute mental states to others

- Development: Emerges around age 4–5 (false belief task)

- Neural basis: medial prefrontal cortex, temporoparietal junction (TPJ), posterior cingulate cortex

Demonstration:

- Sally-Anne Test

Real-Life Examples:

- Social faux pas, sarcasm, misunderstandings

Larger relevance:

- Subjectivity and Interpretation: Theory of Mind is not just about understanding what others think, but also that others can experience the world differently from us.

- Constructed Reality: Our understanding of the world is filtered through our own mental models—and we extend this modeling to others. Cognitive science suggests that we construct mental representations of other people’s beliefs, intentions, and emotions, which in turn influence how we interpret events, predict behavior, and assign meaning.

- Social Reality and Belief Systems: Shared beliefs (e.g., social norms, institutions, culture) rely on mutual Theory of Mind. We assume others think like we do—or at least that we can model their thinking

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” — Ludwig Wittgenstein (Theory of Mind may help us imagine beyond those limits.)

Section 2: Empathy and Emotion Sharing

Core Concept: We feel what others feel — or think we do

- Emotional mirroring: facial mimicry, mirror neurons

- Embodied cognition: Theories of embodied cognition suggest that we simulate others’ experiences using our own sensory and motor systems. Mirror neurons may help us “try on” others’ emotions by triggering internal states that match what we observe.

- Suggested Brain areas: anterior insula, ACC

- Brain regions like the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) are involved in sensing one’s own body and monitoring internal states.

Emotion Synchronization:

- Shared physiological responses: heart rate, skin conductance

- Collective emotion in concerts, rituals, protests

Section 3: Miscommunication and Bias

Core Concept: Our assumptions color our perceptions

- Egocentric bias: assuming others see things our way

- The Curse of Knowledge: hard to imagine not knowing what you know

- Cultural differences: emotion expression norms

How this relates to our past lectures and discussions:

- Reality Is Negotiated, Not Given: According to Shared Reality Theory, people are motivated to establish common inner states—beliefs, feelings, attitudes—with others. We seek out and maintain shared realities to reduce uncertainty, foster belonging, and coordinate action. But when assumptions go unchecked, this process can fail.

- Egocentrism Is the Default: Even with developed Theory of Mind, we often anchor too strongly in our own knowledge and perspective. This leads to phenomena like the curse of knowledge (forgetting what it’s like not to know something) and egocentric bias (assuming others see what we see), both of which disrupt shared understanding.

- Miscommunication Erodes Shared Reality: When we incorrectly assume shared knowledge, misinterpret emotional signals, or ignore context, shared reality breaks down.

The Paradox: We long to connect and co-construct meaning, yet our minds are wired in ways that often get in the way. Does recognizing these limits help us repair and maintain shared realities more intentionally?

Section 4: Tools for Studying Shared Experience

Hyperscanning:

- Recording multiple brains simultaneously (e.g., during conversation)

- Studies show neural synchrony linked to cooperation and understanding

Naturalistic Paradigms:

- Story listening, music, live interaction

- Neural alignment = shared interpretation

Highlighted Study:

- Sievers et al., 2025: Brain-to-brain coupling during consensus making

Section 5: Translating Brain to Experience

Core Concept: Brain activity isn’t the same as experience

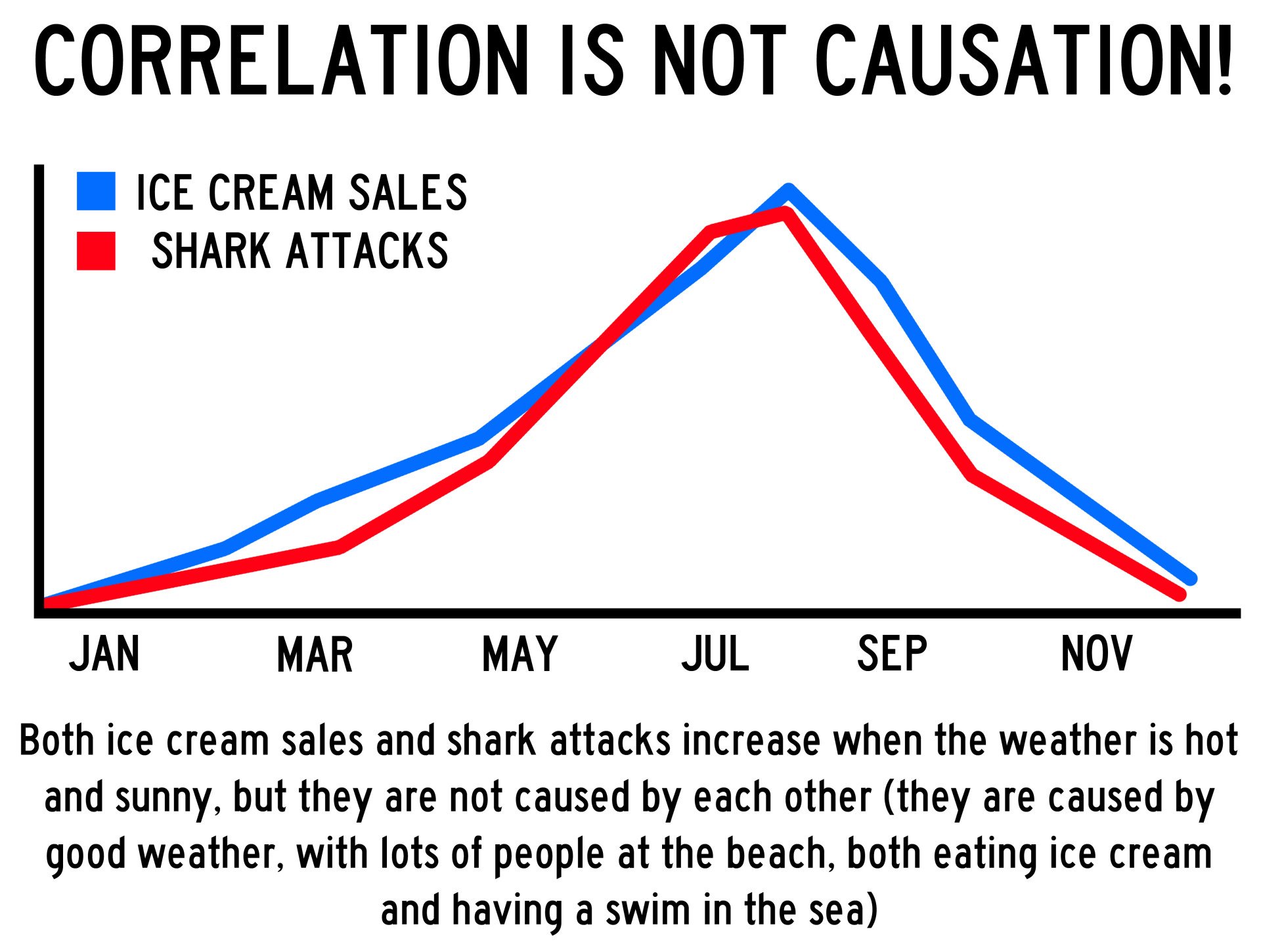

- Correlation vs. Causation: Brain activity that correlates with experience isn’t necessarily causing it

- The Binding Problem: How distributed neural signals create unified awareness

- Individual Differences: No two brains are wired the same

- Observer Effect: Studying consciousness may change it

Philosophical Questions:

- Can we truly “read” thoughts?

- Is a brain scan showing a thought or just a pattern?

- How do we bridge the “explanatory gap”?

Section 6: Future of Technology

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs)

-

Restoring Function: Thought-controlled robotic limbs, speech decoders, and direct “brain typing” are giving paralyzed patients new ways to interact with the world.

- Expanding Agency: BCIs may blur the line between thought and action—where does the body end and the interface begin?

- blog post on it is linked

- Redefining Communication: As decoding brain signals improves, the promise is that our internal states may become directly translatable into action or shared experience.

Demos:

The Cognitive Cost of AI: Use It or Lose It?

- Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT are reshaping how we write, plan, and even think. But there’s a growing concern: Are we offloading too much?

“The biggest AI threat? Young people who can’t think.” Wall Street Journal article

-

Students increasingly rely on AI for language, synthesis, and reasoning. While this can be empowering, overuse may reduce deep processing, critical thinking, and even metacognition.

-

Cognitive Offloading is not new (think: calculators, maps, Google). But LLMs may offload the thinking process itself—and with it, our ability to model, reflect, and adapt.

-

A 2024 study from MIT (“Your Brain on ChatGPT”) linked here was covered broadly by the media and is a good starting point for how to think about these issues

-

Do you empower students to learn how to use these tools? Should they even be used in the classroom? Let’s discuss!

Broad End of Class Discussion: Why This Research Matters

Clinical Impacts

- Predicting treatment response for depression

- Monitoring anesthesia awareness

- Understanding altered perception in schizophrenia

Societal Applications

- Emotion-sensitive virtual reality

- Thought-responsive games

- Adaptive learning in education

- Attention tracking for transportation safety

Scientific Relevance

- Deepening debates in philosophy of mind

- Guiding ethical AI development

- What does it even mean to be human?

Additional Resources

Books:

- “Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect” by Matthew Lieberman

- “The Empathic Brain” by Christian Keysers