Lecture 2- Measuring the Unmeasurable - How Scientists Study Inner Experience

“The brain is the last and grandest biological frontier, the most complex thing we have yet discovered in our universe.” - James Watson

Objectives

- Understand the challenge of studying subjective experience objectively

- Learn about neuroimaging techniques in accessible terms

- Explore how scientists bridge the gap between brain activity and conscious experience

- Discover innovative methods for measuring emotions, memories, and perceptions

- Consider ethical implications of “mind reading” technology

The Hard Problem of Consciousness

Discussion Starter

- The “Hard Problem”: Explaining why we have subjective experiences at all

- The “Easy Problems”: Measuring behavior, brain activity, responses

- The Gap: How does neural firing become the feeling of seeing red?

What is consciousness

Key Questions We’ll Explore:

- How do we study something only you can experience?

- What can brain scans actually tell us about your inner life?

- How close are we to “reading minds”?

🧠 Deep Dive: Why the Brain?

I. Introspection is hard

• (Why can’t we just ask them about it?)

• Hard to figure out why people are thinking something

II. Brain is causal

• Can change something about the brain and then change something about subjective experience

• Can stimulate the amygdala and change people’s valence judgements

• Can alter preferences

Section 0: Deep Dive –> Dreams

- Inspired by last week’s discussion, here’s what I have found as the most “up-to-date” discussion on dreams and how it fits into today’s broader discussion:

- Review paper from Scarpelli et al, 2022 discussed the following:

- Dreaming is defined as “a composite experience occurring during sleep that includes images,sensations, thoughts, emotions, apparent speech, and motor activity”

- Early research (e.g., Hobson et al., 2000) linked dreaming primarily to REM sleep based on EEG findings (we’ll return to this below). However, more recent studies challenge this view. For example, dreams have been reported during NREM sleep, and dreaming persists even when REM-related brain regions are lesioned or when REM sleep is pharmacologically suppressed. These findings suggest that dreaming is not exclusive to REM sleep and may occur across multiple stages of sleep.

- It’s been suggested that REM and NREM have different qualitative aspects of dreams:

- REM: “emotional, vivid, “dream-like””

- NREM: “thought-like with reduced emotional load, contents more similar to walking thoughts”

- Citation (among many) from the main paper: Foulkes, 1967

- Individual characteristics impact dreaming:

- gender, age can predict how dreams are remembered as well as certain personality traits like openness or predisposition to suppress negative emotions

- Dreams have also been linked to different anaotmical differences in the structures of the hippocampus and the amygdala or have different white matter volume.

- Main idea: physiological state preceeding dream recall seems to be the most important

- Continuity Hypothesis of Dreaming: proposes that our dreams reflect elements of our waking life—such as personal experiences, emotions, concerns, and thoughts. This idea stands alongside the older activation hypothesis, which focused more on brain activity patterns during sleep

- Day-residue effect: Dream content reflects experiences from the past 1–2 days.

- Dream-lag effect: Dreams incorporate experiences from 5–7 days prior, especially in REM sleep.

- Brain mechanisms involved in memory and emotion during wakefulness appear to function similarly during sleep.

- EEG studies link theta and alpha activity to dream recall and memory encoding, echoing patterns seen in waking episodic memory processing.

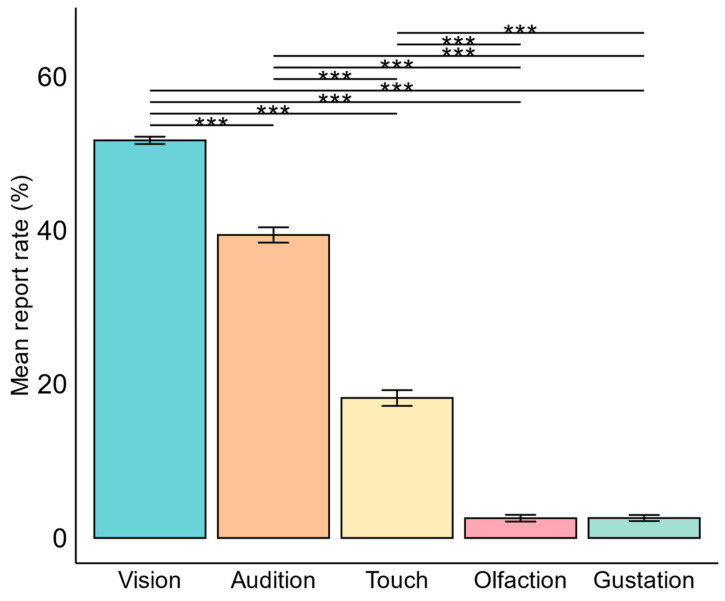

- Both pre-sleep and during-sleep stimuli (e.g., images, sounds, smells, touch) can influence dream content.

- Notably, olfactory stimuli (smells) influence emotional tone in dreams due to their direct connection to the limbic system.

- Dreaming is defined as “a composite experience occurring during sleep that includes images,sensations, thoughts, emotions, apparent speech, and motor activity”

Figure from: Heijden et al., (2024)

Figure from: Heijden et al., (2024)

Setting up for today: Can we directly access dream experience (and subjective experience more broadly?)

- Directly studying dreams is challenging because dreams are subjective and not observable in real time (making them harder than most other ideas). Most research focuses on dream recall, not the dream itself.

- Methods of Studying Dreams:

- Retrospective reports (e.g., questionnaires) – fast but prone to memory bias.

- Prospective reports (e.g., dream diaries) – better for identifying consistent dream recallers.

- Awakenings during sleep (with polysomnography) – most precise method; allows researchers to correlate EEG patterns with reported dream content.

- A new line of research looks at dream-enacting behaviors (DEBs; Baltzan et al., 2020)—physical, verbal, or emotional actions during sleep—as possible direct expressions of dreams:

- REM Behavior Disorder (RBD), sleepwalking, and nightmares often involve actions that reflect dream content and can therefore be used to study dreams.

- Studies show strong alignment between movements or facial expressions during sleep and later dream reports (Rivera-García et al. (2019)).

- For instance, facial muscle activity (e.g., frowning, smiling) during REM sleep correlates with dream emotion.

Section 1: The Neuroimaging Revolution - Windows Into the Living Brain

Core Concept: Technologies That Let Us See Thoughts

1.1 Functional MRI (fMRI) -

How It Works - Simple Explanation:

- Measures blood flow (more active areas need more oxygen)

- Like watching a city from space - busy areas light up

- Takes a “brain photo” every 2-3 seconds

- Creates colorful maps of brain activity

What fMRI Can Show Us:

- Which brain areas activate when you get different inputs

- How your brain responds to emotions

- What happens when you make decisions

- Differences between rest and active thinking

Fun fMRI Studies to think about:

- Political Brains: How Democrats and Republicans process political information differently

1.2 EEG -

How It Works:

- Measures electrical activity from neurons

- Like listening to a symphony orchestra from outside the concert hall

- Records brain waves in real-time (millisecond precision)

- Shows timing of mental processes

Types of Brain Waves:

- Alpha waves: Relaxed, meditative states

- Beta waves: Active, focused thinking

- Theta waves: Deep meditation, REM sleep

- Gamma waves: Sometimes linked to Moments of insight, “aha!” experiences

Other Cutting-Edge Techniques:

- Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS): Portable brain monitoring

- Magnetoencephalography (MEG): Measures magnetic fields from brain activity

-

Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI): Maps brain’s white matter highways

- Will show local documents off computer from intracranial stimulation studies

Comparison Chart:

| Technique | Time Resolution | Spatial Resolution | What It Measures | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | Seconds | Millimeters | Blood flow | Location of activity |

| EEG | Milliseconds | Centimeters | Electrical activity | Timing of thoughts |

| PET | Minutes | Millimeters | Metabolism | Neurotransmitters |

Section 2: Creative Approaches to Studying Subjective States

Core Concept: Clever Ways to Measure Inner Experience

2.1 Measuring Emotions - The Feeling Detectives

Multi-Modal Emotion Detection:

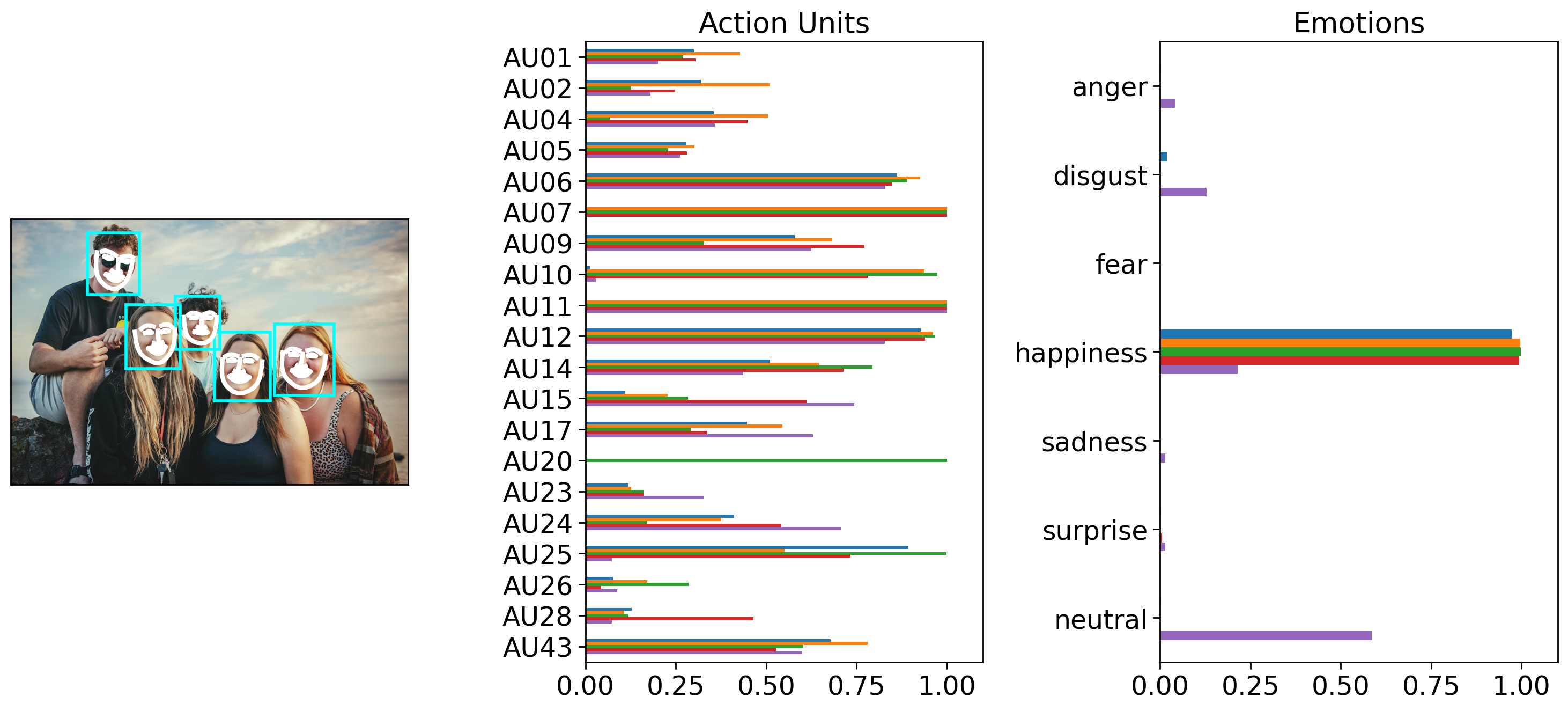

Facial Expression Analysis:

- Facial Action Coding System (FACS)

- Automated emotion recognition software

- Micro-expressions that reveal hidden emotions

-

The Facial Action Coding System (FACS), developed by Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen, is a scientific tool used to classify facial expressions based on the movement of individual facial muscles. Instead of labeling emotions directly, FACS breaks down expressions into Action Units (AUs)—the building blocks of facial movement. For example, AU12 (lip corner puller) is typically associated with smiling, while AU4 (brow lowerer) often reflects frowning or concentration.

-

FACS is widely used in fields like psychology, law enforcement, autism research, and artificial intelligence to analyze expressions with precision. It’s especially helpful for detecting micro-expressions—fleeting facial movements that may reveal hidden emotions. However, it’s important to note that emotion interpretation is context-dependent: the same Action Unit can signal different feelings depending on cultural norms or social setting. A smile might indicate joy, embarrassment, or even sarcasm depending on the situation.

- New(ish) Dartmouth technology – pyfeat:

Physiological Measures:

- Heart Rate Variability: Emotional stress indicators

- Skin Conductance: Arousal and excitement

- Eye Tracking: What emotions draw our attention

Interactive Demonstration:

- Emotion Recognition Test

- Real-time Emotion Detection - Camera-based emotion analysis

Affective Computing

🤖 Deep Dive: Affective Computing

Affective computing is a field at the intersection of computer science, psychology, and cognitive science that focuses on building systems that can recognize, interpret, and respond to human emotions. These systems aim to bridge the gap between humans and machines by giving technology the ability to process affective (emotional) information.

Affective computing applications range from facial expression analysis and voice tone recognition to wearable sensors that detect physiological changes (like heart rate or skin conductance). The goal is to enable machines to adapt their behavior in ways that feel more intuitive and empathetic to human users. This technology is increasingly used in areas like mental health, education, customer service, and human-computer interaction research.

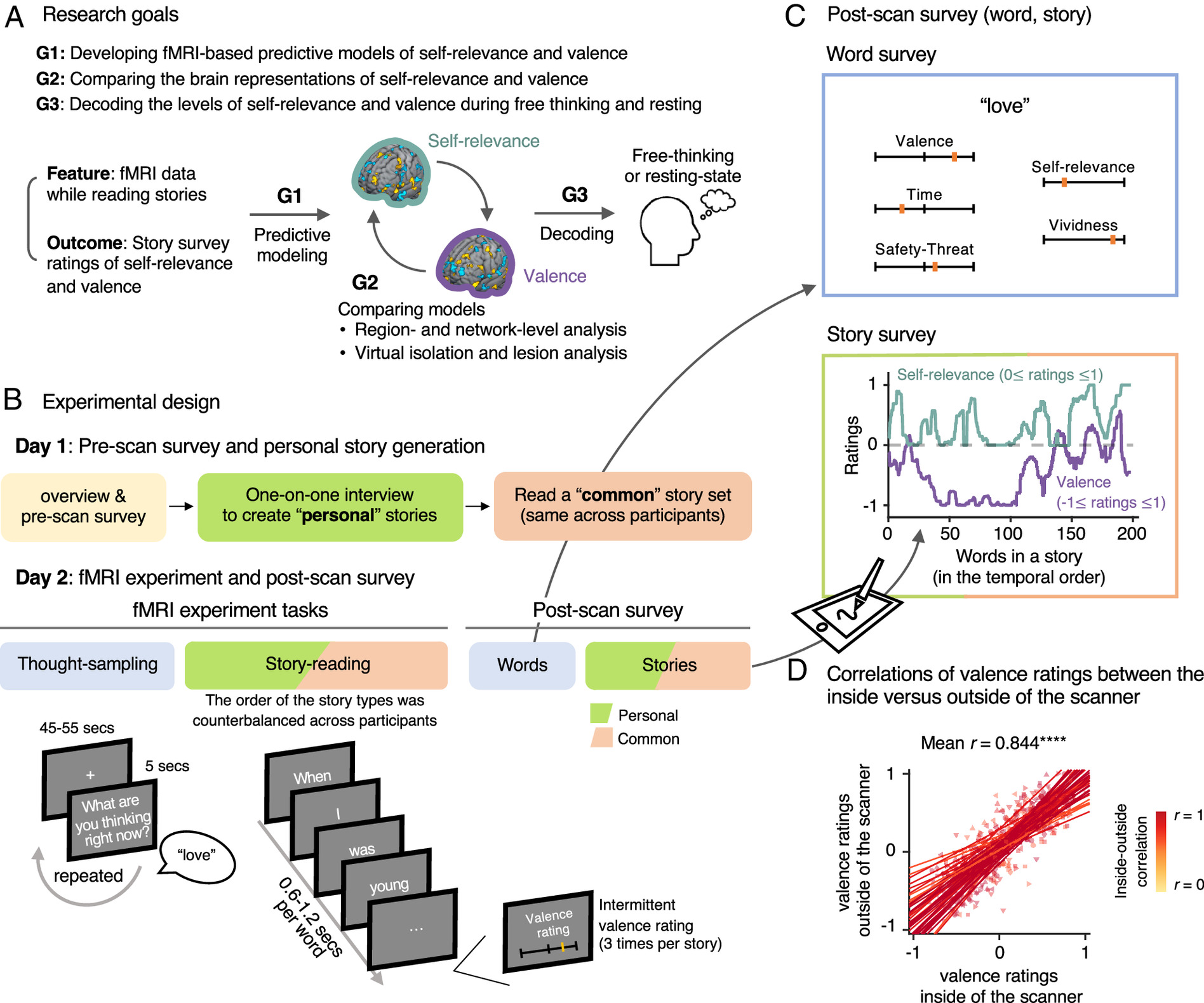

Thought Sampling Experiments Thought sampling is a method used to study the contents of consciousness by prompting individuals to report their current thoughts at random or predetermined times. These experiments offer a window into spontaneous, self-generated cognition—such as mind-wandering, inner speech, and imagery.

🔍 Why Use Thought Sampling? The human mind rarely stays focused on external tasks; instead, it frequently shifts to internal thoughts (e.g., daydreaming, planning, self-reflection).

Thought sampling helps researchers quantify and categorize these internal experiences, which are otherwise difficult to access. | Method | Description | | —————————————– | ————————————————————————————–

🧪 Common Methods

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Experience Sampling Method (ESM) | Participants are “pinged” at random moments and asked what they are thinking. |

| Descriptive Experience Sampling (DES) | More structured and in-depth, often with follow-up interviews about the sampled thought. |

| Probe-Caught Mind-Wandering | Participants are interrupted during a task and asked whether they were on-task or off-task. |

| Self-Caught Mind-Wandering | Participants report when they notice their mind has drifted. |

Example experimental set-up from: Kim et al., 2020

2.2 Studying Memory -

Types of Memory Studies:

- Episodic Memory: Remembering specific life events, including autobiographical memories

- Semantic Memory: General knowledge and facts

- Working Memory: Holding information temporarily

Interactive Elements:

- Memory Palace Technique - Ancient memory method

- False Memory Test - How easy it is to implant false memories

“Breakthrough” Research:

- Memory Reactivation: How sleep consolidates memories

- Memory Editing: Changing traumatic memories in PTSD

- Collective Memory: How groups remember events differently

🧭 Naturalistic Approaches to Memory

- Traditional memory experiments often rely on artificial lists of words or images, presented in controlled lab settings. But real-life memory doesn’t work that way — we remember stories, people, emotions, and unfolding experiences.

- Recent research has moved toward more naturalistic paradigms, which aim to study memory as it operates in everyday life. Examples include:

- Watching movies or listening to stories in the scanner to study how the brain tracks and recalls complex, dynamic narratives

- Virtual reality tasks that simulate real-world environments

- Autobiographical memory interviews that tap into personally meaningful life events

- Shared narrative recall, where people remember the same experience (e.g., a film or news event) and researchers examine how memories align or differ across individuals

- These approaches allow researchers to:

- Study event boundaries (how we segment continuous experience into discrete memories)

- Track memory over time and in context

- Use machine learning to decode brain activity during real-world events

- Understand how prior knowledge or schemas shape what we remember

- (First part): Interesting interview with a graduate student about their project using movies to study subjective experience

2.3. 📊 Within-Subject Approaches

-

Much of cognitive neuroscience focuses on group-level effects, but subjective experience varies dramatically across individuals. A within-subject approach allows researchers to track how a single person’s thoughts or internal states shift over time or across contexts. This is especially useful when studying:

- State fluctuations (e.g., alertness, emotion, fatigue)

- Effects of experimental manipulations (e.g., context shifts like the Mooney images we talked about last week, mindfulness training, pharmacological interventions)

- Natural transitions (e.g., from wake to sleep or during moments of insight)

Discussion Questions

Personal Reflection Questions:

-

Have you ever tried to explain a dream, emotion, or train of thought and felt frustrated by how inadequate language was to describe it? Why do you think that is?

-

When you “zone out” or daydream, how would you describe what your mind is doing? Do you think a brain scanner could ever fully capture that experience?

Application Questions:

-

Should mental health treatments rely more on subjective reports or brain-based measures — or both? What are the pros and cons of each?

-

If you were designing a technology to detect or interpret someone’s internal thoughts, what ethical issues would you need to consider?

Critical Thinking Questions:

-

Can we ever truly measure subjective experience? Or are we always reconstructing it from imperfect proxies (like words, behavior, or brain activity)?

-

If subjective experience is always filtered through personal, cultural, and situational lenses, how do we do science on it at all?

-

Is it possible that some aspects of experience are fundamentally ineffable? What does that mean for psychology or neuroscience?

Additional Resources

Books for Further Reading:

- “The Conscious Mind” by David Chalmers - The hard problem of consciousness

- “Incognito” by David Eagleman - The unconscious brain

- “Being You” by Anil Seth - Contemporary consciousness research and a decently easy read!

Online Resources:

- BrainFacts.org - Society for Neuroscience educational site

- Allen Brain Institute - Interactive brain atlases

Interactive Experiences:

- Virtual Brain - Explore real brain data

- Cognitive Fun - Brain games and consciousness tests

- Participate in research - Participate in ongoing research on morality

- Participate in my research - In-person study at the Hood Museum