Lecture 1- Our brains construct reality

“We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.” - Anaïs Nin

Objectives

- Understand that perception is active construction, not passive recording

- Explore how past experiences shape present perceptions

- Discover why eyewitness accounts can differ dramatically

- Examine how culture shapes our fundamental perception of reality

The Dress That Broke the Internet

The Phenomenon

Do you see blue and black? White and gold? Why do you think this happens?

- It a matter of the brain’s interpretation of what your eyes are seeing

- Perception of reality is not the same thing as reality

-

The Dress phenomenon refers to a viral internet sensation from 2015 where a photograph of a dress sparked massive global debate about its colors. While some people perceived the dress as blue and black, others saw it as white and gold, with roughly equal numbers in each camp. This wasn’t simply a matter of opinion—people were genuinely seeing different colors in the identical image. The phenomenon occurs due to individual differences in how brains process ambiguous lighting information and make assumptions about the illumination source. When the brain interprets the dress as being in shadow, it compensates by perceiving lighter colors (white and gold), but when it interprets the dress as being in bright light, it sees the actual darker colors (blue and black). The Dress became a perfect real-world example of how individual brains construct different subjective realities from identical sensory input, demonstrating that perception is an active, interpretive process rather than a passive recording of objective reality.

- Useful summary video:

The Science Behind It

- Lighting assumptions: Your brain makes assumptions about the lighting conditions

- Color constancy: How your visual system adjusts for different light sources

- Individual differences: Age, screen settings, and personal color processing variations

- Color constancy explanation:

- Figure from: Brainard & Hurlbert, 2015

- Linked paper here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982215005941

🔬 Deep Dive: Color Constancy Explanation

The color constancy explanation for "The Dress" centers on how our brains automatically adjust for different lighting conditions to maintain stable color perception. Color constancy is a property where our visual system tries to make objects appear the same color under different lighting conditions by making assumptions about the illumination source and mentally "subtracting" or "discounting" the color cast of the light.

For The Dress specifically, the explanation works as follows: People who saw the dress as white and gold probably assumed it was lit by cool, bluish daylight, so their brains ignored shorter, bluer wavelengths. Those who saw it as blue and black assumed warm, artificial light, so their brains ignored longer, redder wavelengths.

The mechanism is that shadows are blue, so people who assume the dress is in shadow mentally subtract the blue light to view the image, which then appears in bright colors — gold and white. However, artificial light tends to be yellowish, so if people see it as brightened by artificial light, they factor out this yellow color, leaving a dress that appears black and blue.

Section 1: Your Brain as Reality Constructor

Core Concept: Perception isn’t Photography - It’s Painting

1.1 Change Blindness

Essential Videos :

- Change Blindness in Real Life - The monkey study

- Change Blindness in Real Life #2 - this video is better and gives a fantastic explanation

- Change blindness is our failure to notice large changes in our visual environment. It occurs when changes happen during eye movements, brief interruptions, or gradual transitions

- This phenomenon reveals the limitations of our visual attention and memory

Bigger picture:

- You feel like you see everything clearly and completely - but you don’t

- Your brain creates a rich, detailed experience from limited, fragmented information

- This isn’t a bug in the system - it’s a feature that allows us to function efficiently

- What you experience as “reality” is actually your brain’s best guess about what’s out there

Discussion Points:

- Why didn’t participants notice the person changing?

- What does this tell us about how much we actually “see”?

- Real-world implications: driving, witnessing events

1.2 Perceptual priors – Mooney Images Demonstration

- Key Point: Prior knowledge dramatically changes what we see

- Mooney Explanation – NYU Langone

Swipe or click dots to navigate

Mooney images are high-contrast, black-and-white images that initially appear ambiguous or meaningless. However, once we’re told what they represent—or once our brain figures it out—we can’t unsee the hidden image. This phenomenon demonstrates how perceptual priors—our brain’s pre-existing expectations and knowledge—play a crucial role in shaping what we see. Rather than passively receiving information from the world, perception is an active process, influenced by what we expect to be there. Mooney images remind us that our visual experience is not just about what hits the retina—it’s about what the brain makes of it.

Another example:

The McGurk Effect is a striking example of how our expectations and prior experiences shape what we perceive. When a person hears the sound “ba” but sees a video of someone saying “ga,” they often report hearing a completely different sound—“da.” This illusion arises because the brain automatically integrates visual and auditory information, using prior knowledge that mouth movements and sounds should match. Rather than relying solely on the sound, the brain’s multisensory priors override the auditory input to create a new, fused percept. The McGurk Effect shows that what we hear is not just about sound—it’s a product of what we expect to hear, reinforcing the idea that perception is an active, constructive process.

Section 2: The Role of Memory in Perception

Core Concept: Past experiences shape what and how we see

Our perception is not just a passive process of receiving information from the world. Instead, the brain uses prior experiences, knowledge, and expectations—in other words, memory—to actively interpret sensory input. This is what makes perception efficient, but also biased and subjective.

2.1 Developmental Differences in Memory

Case Study: The Birthday Party Experiment

Depending on age, people remember and perceive the same event very differently:

- Children: Focus on vivid, immediate sensory input—cake, balloons, games

- Teenagers: Focus on social dynamics—who was there, who said what, any embarrassment

- Adults: Focus on broader themes—relationships, meaning, planning, emotions

This highlights how memory influences not only what is encoded, but also what is noticed in the first place.

🔬 Deep Dive: Schemas and developmental differences

Schema Theory (Bartlett, 1932): People interpret new experiences using existing knowledge frameworks, which differ with age. - A child’s “party schema” includes cake and games, while an adult’s might involve social meaning or planning..

Young children tend to focus on salient, sensory-rich details (like decorations or candy). Older children and adults are more likely to recall thematic and social elements.

- See: - Fivush, R. (1991). The development of memory for emotionally significant events. - Nelson, K. & Fivush, R. (2004). The emergence of autobiographical memory: A social cultural developmental theory.Autobiographical Memory Studies: Adults and children asked to recall the same event (like a birthday or field trip) show age-related differences in both content and structure of memory.

- See: - Bauer, P. J., & Larkina, M. (2016). The onset of childhood amnesia in childhood: A prospective investigation of the course and determinants of forgetting of early-life events. - Reese, E. (2002). Social factors in the development of autobiographical memory: The state of the art.2.2 Expertise and Selective Attention

The Radiologist Example

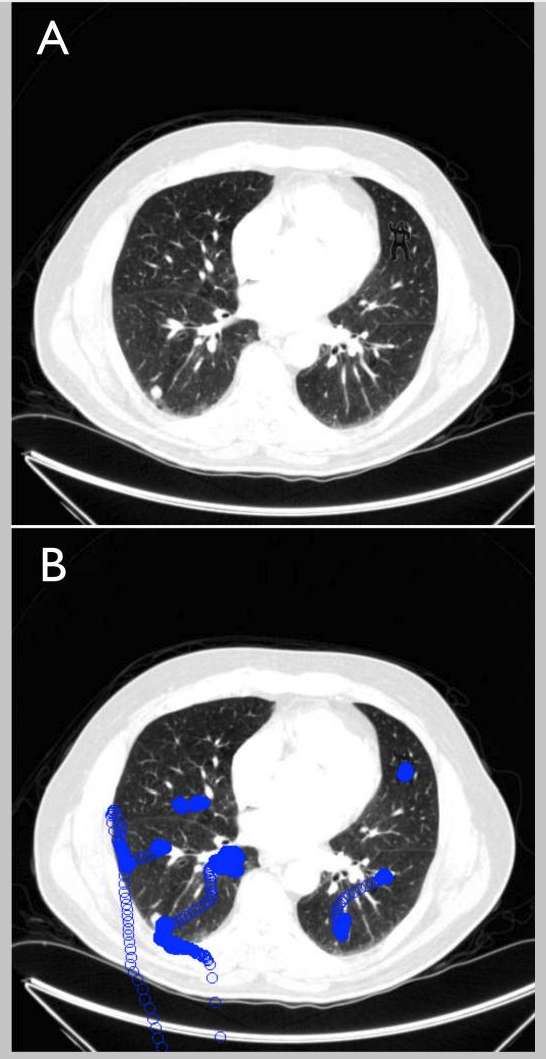

Radiologists were shown an image of a lung scan with a tiny image of a gorilla embedded. 83% missed it entirely.

Why? Because their memory-trained perceptual systems were honed to detect tumors—not gorillas.

X-ray paper; Drew, Ho & Wolfe, 2014

Figure from Drew, Ho & Wolfe, 2014

Figure from Drew, Ho & Wolfe, 2014

Expertise and Narrowed Perception in Music

Expertise in music sharpens attention to specific sound features like pitch and rhythm, allowing musicians to detect subtle technical details that non-experts might miss. However, this focused attention can also narrow perception, causing experts to overlook broader aspects such as emotional expression or overall musicality. This selective filtering, similar to the “expert’s blind spot” seen in other domains, shows how perceptual priors shaped by experience influence what we notice and what we miss in our subjective experience of music.

Discussion Prompt:

How can expertise both improve and narrow perception?

2.3 Memory Primes Perception: You See What You Expect

Our brains are not passive receivers of sensory input; instead, they constantly generate predictions about what we are likely to perceive next based on prior knowledge, recent experiences, and the current context. This predictive processing is especially important when sensory information is ambiguous, incomplete, or noisy, allowing us to make sense of the world efficiently and quickly.

Classic Study: B vs. 13 Ambiguity

In a famous experiment, an ambiguous character that could be interpreted as either the letter “B” or the number “13” is shown within different contexts. When it appears between the numbers “12” and “14,” people typically perceive it as “13.” However, when placed between the letters “A” and “C,” it is seen as a “B.” This demonstrates how recent context held in working memory strongly influences perception, biasing interpretation toward what is expected or most probable in that situation.

Broader Implications:

- This phenomenon illustrates the brain’s reliance on schemas—mental frameworks developed through experience—that guide perception.

- In everyday life, this means our memories and expectations actively shape what we notice, often filling in gaps or resolving ambiguities based on what we anticipate.

- It also explains why two people can experience the same ambiguous stimulus differently depending on their prior knowledge, culture, or even mood.

- Predictive coding theories in neuroscience further support this idea, suggesting that perception results from a continuous comparison between incoming sensory signals and top-down predictions from memory and context.

Understanding how memory primes perception helps explain many aspects of subjective experience, including why eyewitness testimonies can differ, why we sometimes mishear words, and why learning new contexts can dramatically change what we perceive.

2.4 Schemas: Mental Templates That Shape Perception

A schema is a stored framework or mental model for understanding categories of experiences (e.g., what a classroom, a wedding, or a fast food restaurant is like).

Schemas help us rapidly fill in missing information but can also distort or bias what we notice.

Example: Office Schema Study

Participants were briefly shown a professor’s office. Later, they were more likely to “remember” books that weren’t there—because they expected them to be.

Our memories—and thus our perceptions—can include details that were never actually present, simply because they “fit the story.”

Discussion Prompt:

How might schemas help us navigate daily life more efficiently—and how might they lead to blind spots?

2.5 Loftus and the Malleability of Memory

Memory not only influences perception in the moment, it also affects how we remember past perceptions. This in turn reshapes future perception.

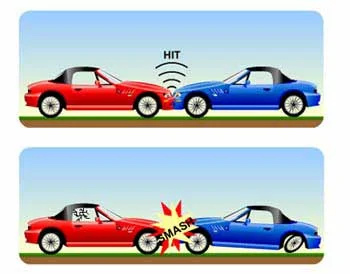

The Car Crash Study (Loftus & Palmer, 1974)

Participants watched a video of a car crash and were asked:

- “How fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?”

vs. - “How fast were the cars going when they hit each other?”

People who heard smashed gave higher speed estimates and were more likely to report seeing broken glass—even though there was none.

Key Insight:

Language and suggestion—even a single word—can alter how we remember what we saw.

Link: Loftus’ Research Summary

2.6 Memory and “Re-seeing” the World

Once a memory is in place, it can retroactively change perception.

- Mooney Images: At first, appear like meaningless black-and-white blobs. But once the object is revealed (e.g., a face), your brain instantly reinterprets what you’re seeing—even though the image hasn’t changed.

- “Aha!” Moments: Once you know what to look for, it’s impossible not to see it.

This shows how perception is not just bottom-up (data-driven) but top-down (experience-driven) as well.

2.7 Neural Evidence for Perception Updating with New Knowledge

Neuroscientific research provides compelling evidence that perception is a dynamic process, continuously updated as new information and insights are integrated. Functional brain imaging studies show that higher-order brain regions involved in memory and cognition, such as the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, interact with sensory areas to modulate perception based on prior knowledge.

A key example comes from studies using Mooney images—ambiguous black-and-white figures that are initially difficult to recognize. Research led by Biyu He and colleagues demonstrated that before participants are informed about what the images represent, activity in early visual cortex remains relatively low. However, once participants learn the correct interpretation, neural activity in both visual and higher-level areas (like the lateral occipital cortex and prefrontal regions) increases markedly, correlating with the subjective “aha” moment of recognition. This suggests that prior knowledge reshapes sensory processing, effectively “unlocking” a clearer perceptual representation.

Similarly, studies (including my own!) show that when participants view the same ambiguous stimulus but bring different personal memories or interpretations, their brain activity patterns diverge, particularly in associative and default mode networks. This aligns with the idea that perception is not only updated by new information but is also shaped by individual history.

Together, these findings emphasize that perception is a constructive and flexible process, deeply intertwined with memory and learning. The brain continuously updates sensory input by integrating new insights, allowing us to reinterpret ambiguous information dynamically.

Summary

- Memory doesn’t just record the past—it actively guides how we see the present.

- Expertise, developmental stage, schemas, and recent context all shape what we notice.

- Sometimes, this leads to efficient perception—other times, to distorted memories or false perceptions.

- Subjective experience is thus a constant negotiation between the world out there and the world we carry inside.

2.8 Cultural Differences in Perception

Perception is not only shaped by biology and individual experience—it is also deeply influenced by culture. Cultural background influences what we pay attention to, how we interpret what we see, and even how we categorize the world.

East vs. West: Fundamentally Different Ways of Seeing

Visual Attention Patterns

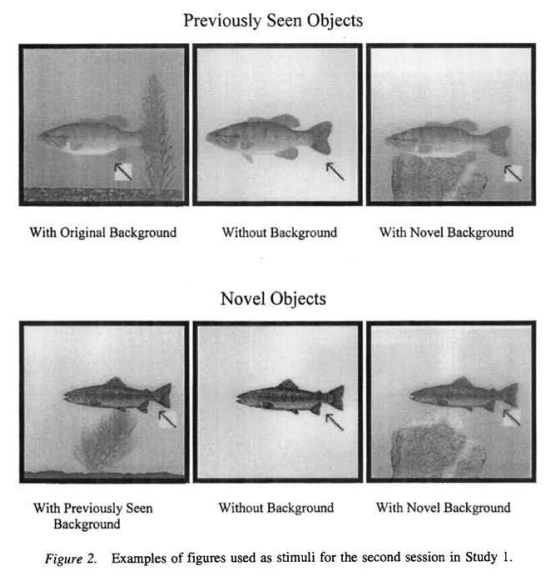

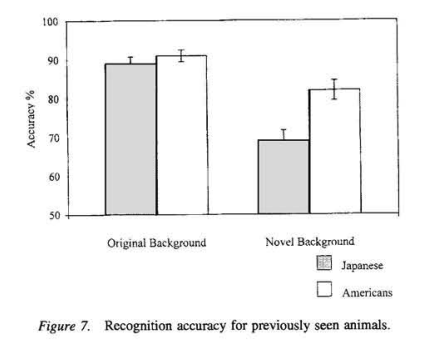

Masuda & Nisbett (2001) conducted a now-classic eye-tracking study comparing American and East Asian participants:

- Western viewers (e.g., Americans):

- Show a tendency toward analytic perception, focusing quickly on the central object (e.g., the big fish in an underwater scene).

- East Asian viewers (e.g., Japanese participants):

- Engage in holistic perception, scanning the background and attending to the context and relationships between elements.

These patterns may reflect broader cultural tendencies: Western cultures tend to emphasize individualism, while East Asian cultures emphasize interdependence and social context (though see disclaimer section below).

Language and Color Perception

Study of the Himba Tribe (Davidoff et al.):

- The Himba people of Namibia use a different color categorization system than English speakers.

- It is believed that they easily distinguish between shades of green that look identical to Western participants, but struggle with blue-green distinctions due to linguistic absence of a separate word for “blue.”

- Another similar study for this is the Russian Blue experiment- Winawer et al, 2007.

This gives some support for the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, which proposes that the structure of a language influences how its speakers perceive and conceptualize the world.

However, it’s important to note that the stronger version of the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis — that language determines thought — has largely been discredited (or has limited support). Instead, most contemporary researchers support a weaker version, suggesting that language influences rather than dictates how we perceive and think about the world. This distinction matters because it allows for the possibility of cross-cultural understanding and cognitive flexibility — even if a concept isn't easily expressible in one's native language, that doesn't mean it's unthinkable.

Videos to Watch:

- Good link

- How Language Changes The Way We See Color? <- good video for class>

Spatial Reasoning and Language

Aboriginal Australian Communities (e.g., Kuuk Thaayorre speakers):

- Use absolute cardinal directions (north, south, east, west) rather than relative directions (left, right).

- Children learn to track directionality extremely early and become experts at orientation.

- As a result, it has been shown that spatial memory and navigation skills outperform those of people in Western societies—even in unfamiliar environments.

- Why this is cool: it extends to other domains!

- Gaby (2012) used comparisions between the Thaayorre, English and bilingual speakers to demonstrate that the language we have for spatial orientation—particularly whether it uses absolute (cardinal) or relative (egocentric) reference frames—influences how we mentally represent time. Crucially, the study suggests that our temporal thinking patterns are shaped by the way we talk about space, not by specific temporal vocabulary, supporting the idea that language indirectly influences cognition through entrenched habits of attention.

Broader Implications and Questions

These findings reveal that perception is not fixed or universal. It is shaped by cultural schemas, which are deeply learned frameworks that influence:

- What we notice

- How we organize information

- What we remember

Discussion Prompts:

- “How might your cultural background influence what you notice in this room right now?”

- “What are the implications of these perceptual differences for eyewitness testimony, cross-cultural communication, or design?”

Key References:

- Masuda, T., & Nisbett, R. E. (2001). Attending holistically versus analytically: Comparing the context sensitivity of Japanese and Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 922–934.

- Davidoff, J., Davies, I., & Roberson, D. (1999). Colour categories in a stone-age tribe. Nature, 398, 203–204.

- Majid, A., Bowerman, M., Kita, S., Haun, D. B. M., & Levinson, S. C. (2004). Can language restructure cognition? The case for space. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(3), 108–114.

- Great paper on linguistic relativity if of interest

⚠️ Disclaimer: Limits of Cross-Cultural Research

While cross-cultural studies in perception offer powerful insights, it's important to approach them with nuance. These findings often rely on broad group comparisons (e.g., "East" vs. "West") that may oversimplify complex individual and cultural differences.

Not all members of a culture perceive in the same way, and cultural identities are fluid, overlapping, and shaped by many factors including education, socioeconomic status, urban vs. rural upbringing, and multilingualism.

In addition, many studies compare small groups of WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) participants to a narrow sample of another culture, which can limit generalizability.

Think about these studies to explore how perception can differ, but avoid treating them as rigid categories or essential traits of any group. Culture is a lens—not a box.

Synthesis and Implications

Why This Matters: Real-World Applications

Eyewitness Testimony

- Wrong identification due to perceptual construction

- How stress, suggestion, and expectation alter memory and perception

- Legal implications and reforms

Cross-Cultural Communication

- Understanding that cultural differences in perception are real and measurable

- Implications for international business, diplomacy, education

- The importance of perspective-taking

Personal Relationships

- Why family members can remember the same event completely differently

Discussion Questions

Personal Reflection Questions:

-

Think of a time when you were certain you saw or heard something, but others disagreed. How might today’s concepts explain this experience?

-

How has your cultural background shaped what you pay attention to or how you interpret situations?

Application Questions:

-

If eyewitness testimony can be unreliable due to how our brains construct reality, how should this impact our legal system?

-

How might understanding cultural differences in perception help in resolving international conflicts or misunderstandings?

Critical Thinking Questions:

-

Is there such a thing as ‘objective reality’ if everyone’s brain constructs their own version of events?

-

How might social media and technology be changing how our brains construct reality?

Additional Resources

Books for Further Reading:

- “The Righteous Mind” by Jonathan Haidt - Cultural differences in moral perception

- “Incognito” by David Eagleman - How the unconscious brain shapes reality

- “The Culture Map” by Erin Meyer - Cultural differences in communication and perception

- See also this link from past courses: https://csavasegal.github.io/osher/DiverseMinds/books/

Online Resources:

- Exploratorium’s Eye Illusions - Interactive visual demonstrations

- Optical Illusions Database - Collection of perceptual demonstrations

Engage in research

- Participate in research - Participate in ongoing research on morality

- Participate in my research - In-person study at the Hood Museum