Lecture- Understanding Schizophrenia

Objectives

By the end of this lecture, students should be able to:

- Understand the basic biology of brain function and neurotransmission relevant to Schizophrenia.

- Define Schizophrenia and understand its epidemiology.

- Describe the neurobiology and pathology of Schizophrenia.

- Discuss the clinical symptoms, diagnosis, and course of the disease.

- Explore treatment options, including pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

- Discuss what we know and what remains unknown about Schizophrenia.

-

Examine current research trends and future directions in Schizophrenia treatment.

Summary Video on Schizophrenia:

1. Basic Biology of Brain Function and Neurotransmission

- Neural Circuits in the Brain:

- The brain relies on intricate circuits involving neurons, synapses, and neurotransmitters for cognition, perception, and behavior.

- Key regions affected in Schizophrenia include:

- Prefrontal Cortex: Important for reasoning, decision-making, and social behavior.

- Hippocampus: Critical for memory formation.

- Thalamus: Relays sensory and motor signals.

- Neurotransmitters and Schizophrenia:

- Dopamine Hypothesis:

- Schizophrenia is associated with hyperactive dopamine signaling in certain brain pathways (mesolimbic pathway).

- Glutamate Dysfunction:

- Abnormal glutamatergic activity in the NMDA receptor may contribute to cognitive and negative symptoms.

- Other Neurotransmitters: Serotonin and GABA also play a role in Schizophrenia.

- Dopamine Hypothesis:

2. Introduction to Schizophrenia

- Definition:

- Schizophrenia is a chronic, severe mental disorder characterized by disturbances in thought, perception, emotion, and behavior.

- History:

- Term coined by Eugen Bleuler in 1911, meaning “split mind” (not to be confused with split personality (dissociative identity disorder)).

- Epidemiology:

- Affects ~1% of the global population.

- Onset typically occurs in late adolescence or early adulthood (18-25 for men; 25-35 for women).

- Equal prevalence across genders but differences in age of onset.

What We Know

- Schizophrenia is a global health challenge, affecting individuals in all cultures.

- It tends to emerge during critical developmental periods (late adolescence).

What We Don’t Know

- The precise combination of genetic, neurodevelopmental, and environmental factors that triggers onset.

3. Neurobiology and Pathology of Schizophrenia

Dopaminergic System

The dopamine system plays a crucial role in regulating mood, motivation, and cognition. In schizophrenia, it is thought to operate abnormally, leading to distinct groups of symptoms:

- Overactive dopamine signaling contributes to psychotic symptoms.

- Dysregulated dopamine may contribute to anhedonia (reduced pleasure) and avolition (lack of motivation), which are part of the negative

-

Note: the striatum does not engage rewards in the same way for schizophrenics that it does for the neurotypical brain

- Mesolimbic Pathway Overactivity: This pathway connects the midbrain to the limbic system, which is involved in emotion and reward processing. Overactivity in this area is linked to positive symptoms, such as hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized thinking. These symptoms are often the most visible and distressing aspects of the condition.

- Prefrontal Cortex Underactivity: The prefrontal cortex is critical for higher-level functions, like decision-making, planning, and emotional regulation. Reduced dopamine activity in this area is associated with negative symptoms, including a lack of motivation, social withdrawal, and blunted emotions. These symptoms are harder to detect but significantly impair quality of life and functional outcomes.

Structural Brain Changes

Advances in brain imaging techniques have revealed significant structural differences in individuals with schizophrenia:

- Enlarged Ventricles: Ventricles are fluid-filled spaces in the brain, and their enlargement suggests a loss of surrounding brain tissue. This reduction is seen as evidence of neurodegeneration or developmental abnormalities.

- Gray Matter Reduction: Specific areas of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and temporal lobes, show a decrease in gray matter volume. These regions are involved in executive functions, memory, and language, explaining some of the cognitive and perceptual challenges faced by individuals with schizophrenia. These structural changes may also worsen as the illness progresses.

Neurodevelopmental Hypothesis

There is evidence that schizophrenia may originate long before symptoms appear, rooted in abnormalities during brain development:

- During prenatal and early childhood stages, factors such as maternal infections, malnutrition, or exposure to stress may disrupt normal brain maturation.

- These disruptions could lead to subtle changes in brain structure and function, which remain dormant until adolescence or early adulthood—periods marked by significant brain remodeling and stress, often coinciding with the first onset of symptoms.

Glutamate Hypothesis

Glutamate, the brain’s primary excitatory neurotransmitter, is increasingly recognized as a key player in schizophrenia:

- Reduced function of NMDA receptors, which are essential for glutamate signaling, can impair communication between neurons. This disruption may contribute to cognitive deficits, such as memory problems and difficulties in attention and learning.

- While dopamine dysregulation is traditionally emphasized, the glutamate hypothesis provides an additional layer of complexity, suggesting that schizophrenia may involve a broader network of neurotransmitter imbalances.

- Interest in glutamate’s role in schizophrenia began when researchers observed that PCP, which interacts with glutamate receptors, induces symptoms similar to those of schizophrenia

The Dysconnectivity Hypothesis in Schizophrenia

The dysconnectivity hypothesis of schizophrenia posits that the disorder arises from disrupted functional and structural connectivity between brain regions rather than localized deficits in specific areas. This perspective contrasts with earlier models that focused on dysfunction in isolated regions, instead emphasizing aberrant communication across large-scale brain networks.

Origins and Rationale

The dysconnectivity hypothesis emerged from neuroimaging and electrophysiological findings showing that schizophrenia is associated with altered coordination of neural activity across distributed brain regions. Early studies using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) revealed widespread white matter abnormalities and impaired functional interactions, particularly in networks supporting cognition, perception, and self-referential thought.

Key aspects of the hypothesis include:

- Abnormal long-range connectivity – Reduced synchrony between distant brain regions, particularly between the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and temporal regions, contributes to deficits in executive function and auditory hallucinations.

- Local hyperconnectivity – Excessive synchronization within certain circuits, such as those within the default mode network (DMN), may underlie self-referential disturbances and psychotic symptoms.

- Imbalance between large-scale networks – Dysfunction in the coordination between the DMN, salience network (SN), and central executive network (CEN) impairs the ability to shift between internally and externally directed cognitive processes.

Neural Basis of Dysconnectivity

Schizophrenia-related dysconnectivity is thought to arise from a combination of:

- Neurodevelopmental abnormalities – Disruptions in synaptic pruning, myelination, and interneuron maturation during adolescence may contribute to connectivity deficits.

- Neurotransmitter dysregulation – Impaired glutamatergic (NMDA receptor hypofunction) and dopaminergic signaling disrupt neural synchrony, leading to inefficient communication between regions.

- White matter integrity deficits – Studies using DTI have shown reduced fractional anisotropy (FA) in major white matter tracts, such as the uncinate fasciculus and corpus callosum, suggesting impaired structural connectivity.

Implications for Symptoms

Dysconnectivity affects various symptom domains in schizophrenia:

- Cognitive Symptoms

- Impaired communication between the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hippocampus disrupts working memory and executive functioning.

- Reduced connectivity within the central executive network (CEN) is linked to difficulties in goal-directed behavior.

- Positive Symptoms (Hallucinations & Delusions)

- Aberrant connectivity between auditory cortex and PFC may underlie auditory hallucinations by impairing self-monitoring mechanisms.

- Hyperconnectivity within the DMN could contribute to delusional thought patterns by reinforcing maladaptive self-referential processing.

- Negative Symptoms (Apathy & Social Withdrawal)

- Disruptions in the salience network (SN) reduce motivation and responsiveness to external stimuli.

- Impaired connectivity in limbic-prefrontal circuits affects emotional regulation and social cognition.

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

The dysconnectivity hypothesis has reshaped schizophrenia research and treatment approaches. Potential applications include:

- Targeting network dysfunctions with neurostimulation – Techniques like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) aim to modulate connectivity between affected brain regions.

- Personalized interventions using connectivity biomarkers – Advances in machine learning and resting-state fMRI may enable individualized treatment based on network-level abnormalities.

- Pharmacological approaches – Beyond traditional dopamine-based treatments, glutamate-modulating drugs (e.g., NMDA receptor agonists) may help restore functional connectivity.

Conclusion

The dysconnectivity hypothesis provides a framework for understanding schizophrenia as a disorder of disrupted neural coordination rather than isolated regional dysfunction. This network-based perspective highlights the importance of integrative approaches to diagnosis, treatment, and future research into schizophrenia.

The Role of the Default Mode Network (DMN) in Schizophrenia

A growing body of research suggests that dysregulation in large-scale brain networks, particularly the Default Mode Network (DMN), plays a critical role in the disorder’s pathophysiology.

What is the Default Mode Network (DMN)?

The DMN is a network of interconnected brain regions that is most active when an individual is at rest and not focused on the external environment. It is involved in self-referential thought, mind-wandering, autobiographical memory, and social cognition. Key nodes of the DMN include:

- Medial Prefrontal Cortex (mPFC) – associated with self-referential processing.

- Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC) / Precuneus – involved in integrating information and maintaining a coherent sense of self.

- Angular Gyrus / Inferior Parietal Lobule – supports episodic memory and perspective-taking.

DMN Dysregulation in Schizophrenia

In schizophrenia, abnormalities in the DMN are well-documented and linked to various symptoms of the disorder. These alterations include:

-

Hyperconnectivity within the DMN

Some studies have reported excessive connectivity within DMN regions, particularly between the mPFC and PCC, which is correlated with positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. This overactivity may lead to an impaired ability to distinguish self-generated thoughts from external stimuli, contributing to the loss of reality testing. -

Reduced DMN-Salience Network Antagonism

The DMN typically exhibits an inverse relationship with the Salience Network (SN), which helps regulate attention and detect relevant stimuli in the environment. In schizophrenia, this balance is often disrupted, leading to inappropriate engagement of the DMN when attention should be directed outward, potentially contributing to cognitive deficits and impaired social functioning. -

DMN-Task Positive Network Imbalance

The Task-Positive Network (TPN), which is active during goal-directed tasks, typically suppresses DMN activity. However, in schizophrenia, studies suggest a failure of DMN deactivation during cognitive tasks, leading to reduced performance in working memory, attention, and executive function.

Clinical Implications

Understanding DMN dysfunction in schizophrenia has significant implications for both diagnosis and treatment. Functional connectivity analyses of the DMN could serve as potential biomarkers for early detection and monitoring of disease progression. Additionally, interventions such as cognitive training, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and pharmacological treatments targeting network dysfunctions may help restore balance between intrinsic and extrinsic brain activity.

What We Know

- Schizophrenia involves a complex interplay of dopamine dysregulation and structural brain abnormalities. These features contribute to the diverse range of symptoms, from hallucinations to cognitive deficits.

- Early life factors, including disruptions in brain development, are likely critical in setting the stage for the illness.

- The involvement of glutamate highlights that schizophrenia is not limited to a single neurotransmitter system, suggesting broader dysfunction in how brain cells communicate.

What We Don’t Know

- The root causes of the initial changes in brain chemistry and structure remain unclear. Are they genetic, environmental, or a combination of both?

- The exact role of glutamate dysfunction and how it interacts with dopamine dysregulation in disease onset is still under investigation.

- Why schizophrenia manifests so differently among individuals—both in symptom severity and response to treatment—continues to be a significant question in the field.

These insights emphasize that schizophrenia is not a single, uniform disorder but a constellation of symptoms and mechanisms that likely require personalized approaches to treatment and intervention.

4. Clinical Symptoms and Diagnosis

- Positive Symptoms (Excess or distortion of normal functions):

- Hallucinations (auditory most common).

- Delusions (false beliefs, e.g., persecution or grandeur).

- Disorganized speech and behavior.

- Symptoms that cause social or occupational dysfunction

- Negative Symptoms (Reduction or loss of normal functions):

- Avolition: Lack of motivation.

- Anhedonia: Reduced ability to experience pleasure.

- Alogia: Reduced speech output.

- Flat affect: Diminished emotional expression.

- Cognitive Symptoms:

- Impaired memory, attention, and executive function (negative symptoms also)

- Diagnosis:

- Clinical evaluation based on DSM-5 criteria:

- Presence of symptoms for at least 6 months with functional impairment.

- Differential diagnosis: Must exclude mood disorders, substance use, and medical conditions.

- Clinical evaluation based on DSM-5 criteria:

What We Know

- Symptoms are categorized into positive, negative, and cognitive domains.

- Diagnosis relies on clinical interviews and observed behavior.

What We Don’t Know

- How to develop objective biomarkers for diagnosis.

- Why symptom severity and progression vary widely across individuals.

The progression of symptomology

(Figure from Tandon et al. (2024)- pdf distributed)

Environmental Factors and Schizophrenia: The Dutch Hunger Winter (1944-1945)

The Dutch Hunger Winter (1944-1945) serves as one of the most well-documented natural experiments in studying the role of prenatal environmental factors in the development of schizophrenia. Research indicates that fetal malnutrition, particularly during early pregnancy, is associated with a significantly increased risk of schizophrenia in offspring.

Key Findings from the Dutch Hunger Winter and Schizophrenia

1. Increased Incidence of Schizophrenia

- Children conceived during the famine (especially in the first trimester) showed a higher risk of developing schizophrenia in adulthood.

- Studies suggest a twofold increase in the risk compared to those conceived before or after the famine.

2. Timing Matters: First Trimester vs. Later Pregnancy

- The risk was highest for individuals exposed to famine during the first trimester of gestation.

- Exposure later in pregnancy (second or third trimester) was associated with weaker or no significant effects on schizophrenia risk.

3. Potential Mechanisms

- Neurodevelopmental Disruptions: Early malnutrition may affect fetal brain development, particularly in pathways related to dopamine and synaptic pruning.

- Epigenetic Modifications: Famine exposure in utero may lead to DNA methylation changes, altering gene expression related to brain function.

- Immune Dysregulation: Poor maternal nutrition may increase susceptibility to maternal infections, which are also linked to schizophrenia.

4. Evidence from Other Famines

- Similar findings have been observed in populations exposed to the Great Chinese Famine (1959-1961), reinforcing the hypothesis that early-life malnutrition increases schizophrenia risk.

- Studies of maternal starvation during World War II in other European populations have also supported this trend.

Implications for Research and Public Health

- The Dutch Hunger Winter studies highlight the critical role of prenatal nutrition in psychiatric disorders.

- They provide strong support for the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia, which suggests that early disruptions in brain development contribute to later disease onset.

- These findings emphasize the importance of maternal nutrition during pregnancy for long-term mental health outcomes.

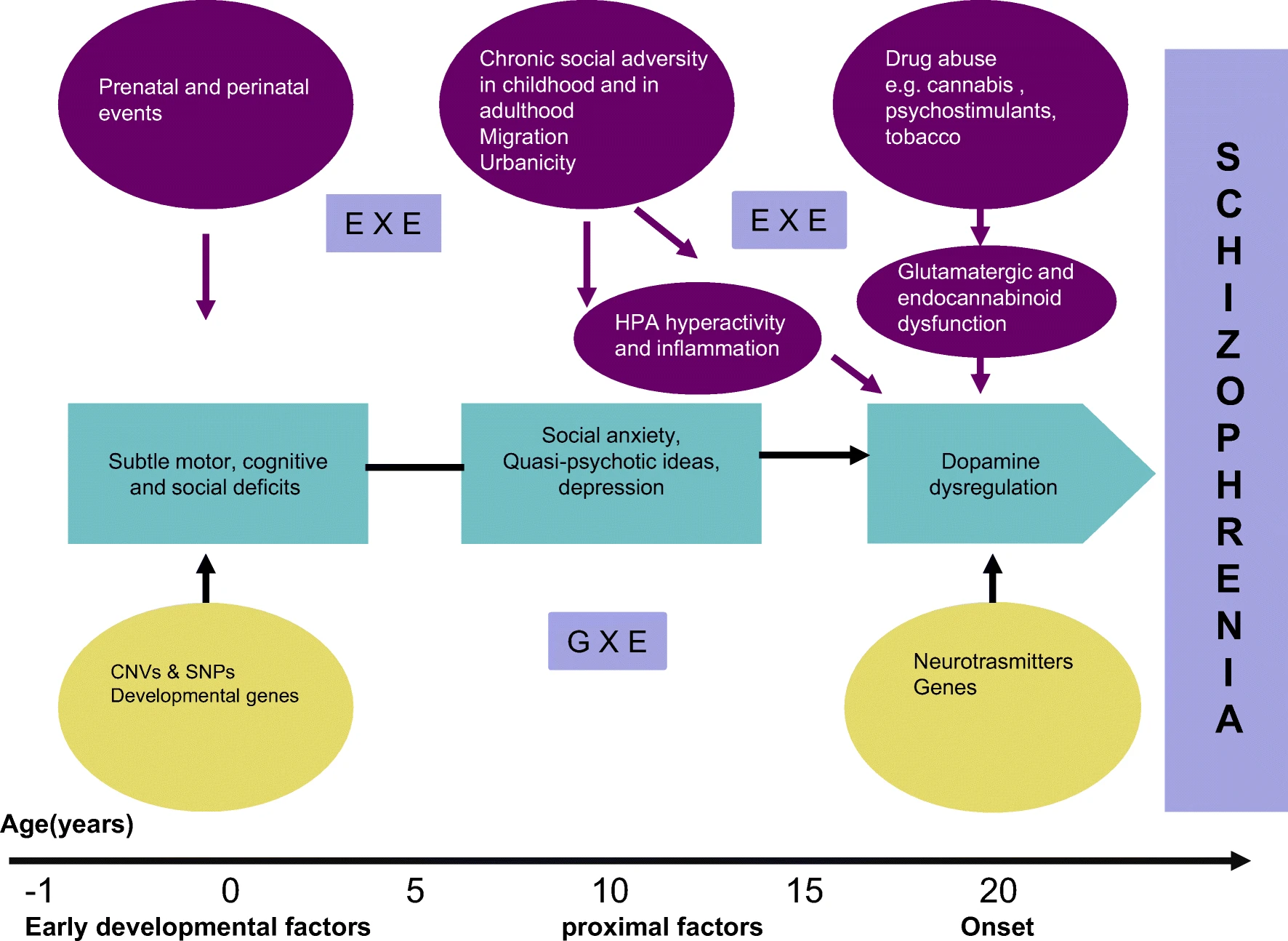

From: Stilo, S.A., Murray, R.M. Non-Genetic Factors in Schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep 21, 100 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1091-3

From: Stilo, S.A., Murray, R.M. Non-Genetic Factors in Schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep 21, 100 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1091-3

6. Treatment and Management

A. Pharmacological Treatments

- Antipsychotic Medications:

- First-generation (Typical): Target dopamine receptors (e.g., Haloperidol).

- Effective for positive symptoms but causes motor side effects.

- Second-generation (Atypical): Act on dopamine and serotonin (e.g., Risperidone, Clozapine).

- Better for negative symptoms with fewer motor side effects.

- First-generation (Typical): Target dopamine receptors (e.g., Haloperidol).

B. Non-Pharmacological Interventions

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Helps manage delusions and hallucinations.

- Social Skills Training: Improves daily functioning and communication.

- Family Therapy: Supports families and reduces relapse rates.

- Lifestyle Interventions: Exercise, diet, and sleep regulation to support overall mental health.

What We Know

- Antipsychotics are effective for managing positive symptoms.

- Psychosocial interventions improve outcomes and quality of life.

What We Don’t Know

- How to treat cognitive and negative symptoms effectively.

- Why some patients are treatment-resistant, even to advanced therapies.

Treatment of Schizophrenia:

Medications for Schizophrenia

- Schizophrenia is primarily treated with medications that target dopamine receptors. These include:

- D2 Receptor Antagonists: Traditional antipsychotics that block dopamine activity, effective in reducing psychotic symptoms like hallucinations.

- D2 Receptor Partial Agonists: Newer medications (e.g., aripiprazole, brexpiprazole) that partially adjust dopamine activity, providing similar benefits with fewer side effects.

- While these medications are effective at managing core psychotic symptoms, they have limited impact on negative symptoms (e.g., lack of motivation) and cognitive difficulties (e.g., memory problems).

- All antipsychotics, except clozapine, have similar effectiveness, but they differ in their side effects. Clozapine stands out for treating severe symptoms that don’t respond to other medications and reducing suicidal thoughts.

- Second-generation antipsychotics have advanced treatment by reducing movement-related side effects seen with older medications.

Psychological and Social Treatments

- Combining medication with therapy and support improves outcomes:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Helps reduce psychotic symptoms like delusions.

- Family Therapy: Reduces relapse rates by involving families in treatment.

- Social Skills Training and Psychoeducation: Boosts everyday functioning and coping skills.

- These treatments are particularly effective when started early in the illness, especially during the first psychotic episode.

New Developments in Treatment

- Non-Dopaminergic Medications:

- Research is moving beyond dopamine-focused drugs. New treatments target other brain systems, such as acetylcholine and glutamate, to address negative symptoms and cognitive challenges.

- Promising medications, like Kar-XT (currently under FDA review), may soon offer new options for patients.

- Early Intervention Programs:

- Early treatment after the first psychotic episode, such as coordinated specialty care, improves long-term outcomes.

- Efforts to identify and treat people in the early stages of psychosis (before full symptoms develop) aim to delay or prevent the onset of schizophrenia.

- Focus on Recovery:

- The ultimate goal is to help people with schizophrenia lead fulfilling, meaningful lives.

- Recovery-focused care emphasizes shared decision-making, individualized treatment goals, and access to comprehensive support services.

Key Takeaway

Treating schizophrenia involves more than just managing symptoms. Medications, therapies, and new approaches work together to improve quality of life, with a growing focus on early intervention and helping individuals achieve their personal goals for recovery.

- Schizophrenia is primarily treated with medications that target dopamine receptors. These include:

The Prodromal Phase of Schizophrenia

The prodromal phase refers to the period before the full onset of schizophrenia, during which early symptoms begin to emerge. This stage can last anywhere from weeks to years and is often marked by subtle cognitive, emotional, and behavioral changes. Identifying the prodromal phase is crucial, as early intervention may help delay or even prevent the progression to full-blown psychosis.

Key Features of the Prodromal Phase

1. Cognitive Changes

- Difficulty concentrating or maintaining attention

- Problems with memory and decision-making

- Increased difficulty processing complex information

2. Emotional and Behavioral Changes

- Withdrawal from social activities and relationships

- Increased anxiety, irritability, or depressive symptoms

- Unusual emotional responses (e.g., inappropriate laughter or flat affect)

3. Perceptual Disturbances and Unusual Thoughts

- Increased suspicion or paranoia

- Mild hallucinations (e.g., hearing faint voices or seeing shadows)

- Odd beliefs or magical thinking (e.g., believing in telepathy or having special powers)

Why the Prodromal Phase Matters

Early detection of prodromal symptoms is crucial for intervention and treatment. Studies suggest that therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), family support, and low-dose antipsychotic medications can help reduce the risk of progression to full psychosis.

Challenges in Identifying the Prodromal Phase

- Many symptoms overlap with common mental health conditions such as depression or anxiety disorders, making early diagnosis difficult.

- Some individuals in the prodromal phase never develop schizophrenia, complicating predictions about who is at the highest risk.

Conclusion

The prodromal phase serves as a critical window for early intervention. Increased awareness and monitoring of early warning signs may improve outcomes and reduce the long-term impact of schizophrenia.

7. Current Research and Future Directions

- Neurobiology:

- Investigating the role of glutamate and NMDA receptor dysfunction.

- Genetics:

- Identification of risk genes (e.g., DISC1, COMT) and polygenic influences.

- Biomarkers:

- Developing brain imaging and blood tests for early diagnosis.

- Novel Therapies:

- NMDA receptor modulators, anti-inflammatory agents, and stem cell therapies.

- Precision Medicine:

- Personalized treatment approaches based on genetic and neurobiological profiles.

What We Know

- Genetic and environmental factors both contribute to Schizophrenia.

- Advanced imaging helps understand brain structure and connectivity changes.

What We Don’t Know

- How to translate emerging therapies into effective clinical treatments.

- Whether early intervention can prevent or reverse disease progression.

8. Summary and Key Takeaways

- Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder characterized by positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms.

- Neurotransmitter imbalances (dopamine, glutamate) and structural brain changes are central to the pathology.

- Current treatments focus on symptom management but do not address the underlying causes.

- Research efforts aim to uncover biomarkers, new therapies, and personalized treatment strategies.

9. Discussion Questions

- Why is Schizophrenia considered a neurodevelopmental disorder?

- Discuss the strengths and limitations of the dopamine hypothesis.

- How might glutamatergic therapies revolutionize the treatment of Schizophrenia?

- Why are cognitive and negative symptoms more challenging to treat?

- What role do genetic and environmental factors play in Schizophrenia risk?

Long and great descriptive video on SZ:

References

- Articles:

- Howes, O. D., & Murray, R. M. (2014). Schizophrenia: An integrated sociodevelopmental-cognitive model. The Lancet, 383(9929), 1677-1687.

- Tandon, R., Nasrallah, H., Akbarian, S., Carpenter, W. T., DeLisi, L. E., Gaebel, W., Green, M. F., Gur, R. E., Heckers, S., Kane, J. M., Malaspina, D., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Murray, R., Owen, M., Smoller, J. W., Yassin, W., & Keshavan, M. (2024). The schizophrenia syndrome, circa 2024: What we know and how that informs its nature. Schizophrenia Research, 264, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2023.11.015

- Insel, T. (2010). Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature, 468, pages187–193. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09552

- Stilo, S.A., Murray, R.M. Non-Genetic Factors in Schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep 21, 100 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1091-3

- Websites:

- National Institute of Mental Health: www.nimh.nih.gov

- Schizophrenia International Research Society: www.schizophreniaresearchsociety.org

- https://www.mcleanhospital.org/essential/schizophrenia Great website!

- Podcasts:

- The entirety of the “Inside Schizophrenia” podcast could be great!