Lecture- Understanding Parkinson's Disease

Objectives

By the end of this lecture, we should be able to:

- Define Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and understand its epidemiology.

- Describe the neurobiology and pathology of PD.

- Discuss the clinical symptoms, diagnosis, and stages of the disease.

- Explore treatment options, including pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

- Discuss what we know and what we don’t yet understand about PD.

-

Examine current research trends and future directions in PD management.

- Useful summary video:

1. Basic Biology of Movement and Neurotransmission

- The Basal Ganglia:

- A group of subcortical brain structures (e.g., striatum, globus pallidus, substantia nigra) involved in motor control.

- The substantia nigra pars compacta produces dopamine, critical for smooth, coordinated movements.

- Role of Dopamine:

- Dopamine acts as a neurotransmitter, enabling communication between neurons in the basal ganglia.

- Loss of dopamine disrupts motor pathways, leading to PD symptoms.

- Also has a role in our GI track (we will come back to this!)

- Neurotransmission in PD:

2. Introduction to Parkinson’s Disease

- Definition: Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a chronic, progressive neurodegenerative disorder primarily affecting movement.

- History:

- First described by Dr. James Parkinson in 1817 as “Shaking Palsy.” He described six individuals with what he considered a novel condition. His original essay can be found here.

- Epidemiology:

- Affects ~1% of people over 60 years old globally. The global prevalence of Parkinson’s disease has been increasing since the 1980s, with a more pronounced rise in the past two decades. The prevalence is higher in more developed countries (Zhu et al., 2024, The Lancet)

- Higher prevalence in males than females. Men are 1.5 times more likely to have Parkinson’s disease than women.

- Incidence increases with age.

- We will discuss why the prevalence may be increasing below

What We Know

- PD is caused by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra.

- The disease affects the motor system and eventually leads to non-motor complications.

What We Don’t Know

- The exact cause of PD remains unclear: Is it primarily genetic, environmental, or a combination?

- Why do some individuals develop PD while others do not, even with similar risk factors?

3. Neurobiology and Pathology of PD

- Key Brain Areas Involved:

- Loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta.

- Reduced dopamine levels in the striatum (part of the basal ganglia).

- Role of Dopamine:

- Dopamine regulates smooth, purposeful movements.

- Pathological Features:

- Presence of Lewy bodies: abnormal protein deposits

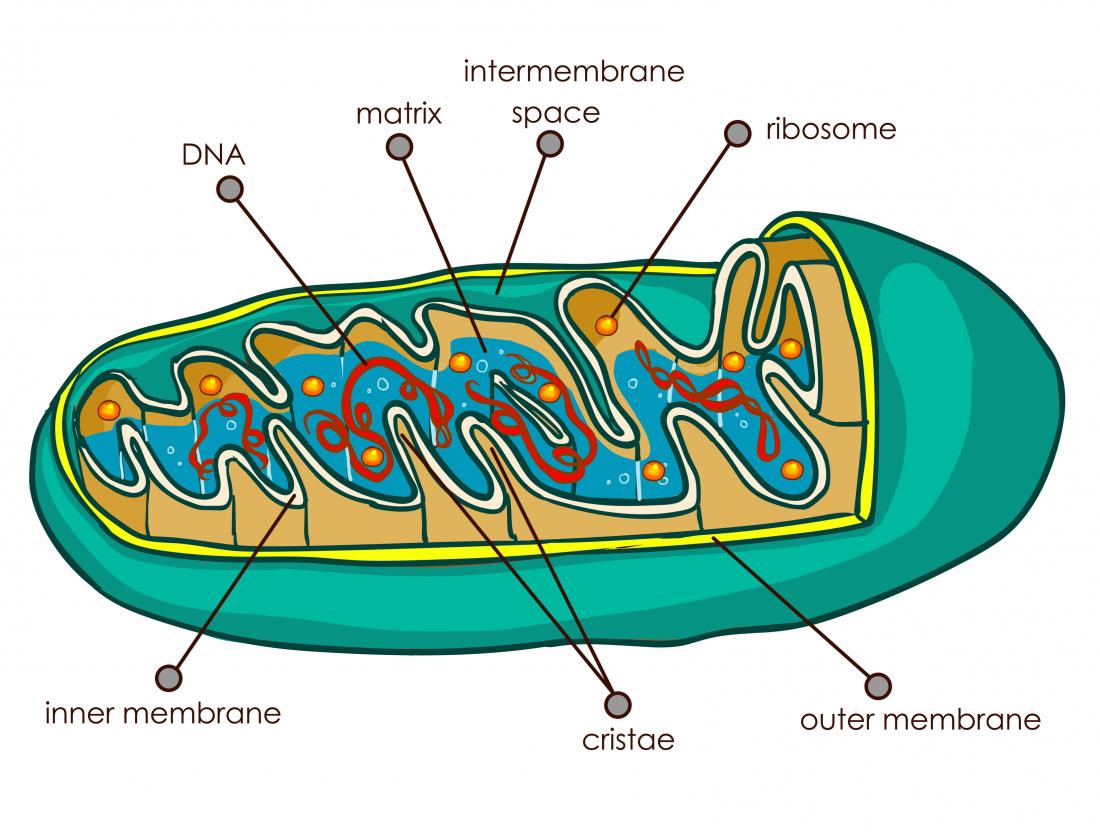

- Neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction.

- When a protein gets misfolded, it leads to further cell death. These appears in the substantia nigra and in other brain regions, as well. (Symptoms are similar to Lewy body dementias, but not identical)

- Key Concept: Loss of ~70-80% of dopaminergic neurons before motor symptoms appear.

-

Figure from Kaitlyn M L Cramb, Dayne Beccano-Kelly, Stephanie J Cragg, Richard Wade-Martins, Impaired dopamine release in Parkinson’s disease, Brain, Volume 146, Issue 8, August 2023, Pages 3117–3132, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awad064.

"In Parkinson’s disease, the nigrostriatal pathway is most affected and results in progressively decreased DA release (top right), and eventually axon degeneration and cell death."

Mechanisms of dopamine release that can go awry

Dopamine release, which is critical for brain function, is often disrupted early. Here’s how it can go wrong:

- Problems with Releasing Dopamine:

- Dopamine is released through a process that depends on specific proteins (SNARE) and energy from mitochondria. In PD, genetic mutations and toxic proteins like α-synuclein disrupt these processes, making it harder for dopamine to be released.

- Trouble Loading Dopamine into Vesicles:

- Dopamine needs to be stored in tiny sacs (called synaptic vesicles) before it can be released. In PD, issues with vesicle loading or moving them to the right place reduce the amount of dopamine available.

- Recycling Problems:

- After dopamine is released, vesicles and leftover dopamine are supposed to be recycled for future use. Mutations in PD interfere with this recycling process, leading to shortages.

- Damage to Dopamine Storage:

- Stress from harmful molecules like reactive oxygen species (ROS) damages the vesicles that store dopamine. This can cause dopamine to leak out and create toxic byproducts, further harming the cell.

- Protein Build-Up:

- PD often involves the build-up of proteins like α-synuclein. These clumps can block important cell functions or trap useful proteins, making it harder for the cell to release dopamine.

- Signals from Other Cells:

- Dopamine release is also influenced by signals from surrounding cells. In PD, changes in these signals—like increased inhibition from GABA, another neurotransmitter—can reduce dopamine release.

What We Know

- Lewy bodies and alpha-synuclein accumulation are central to PD pathology.

- Dopamine loss drives the motor symptoms of PD.

What We Don’t Know

- What triggers alpha-synuclein aggregation? Is it a cause or a consequence of PD? Is it that the protein starts to get misfolded and that causes the neurons to stop dying? Or is that other things cause the neurons to start dying and that then leads to the protein issues, etc.

- Why does PD pathology spread to other regions beyond the substantia nigra (e.g., brainstem, cortex)?

4. Clinical Symptoms and Diagnosis

- Motor Symptoms (Cardinal Features - “TRAP”):

- Tremor: Resting tremor, “pill-rolling” motion.

- Note: if you look back at historical texts, these were mentioned!

- Even Da Vinci wrote about Parkinson’s

- Rigidity: Muscle stiffness, “cogwheel rigidity.”

- Akinesia/Bradykinesia: Slowness or absence of movement.

- Postural Instability: Balance and gait disturbances.

- Tremor: Resting tremor, “pill-rolling” motion.

- Non-Motor Symptoms:

- Cognitive decline, depression, sleep disorders, constipation, hyposmia (loss of smell).

- Clinical Diagnosis:

- Based on history and physical examination.

- No definitive lab test; imaging (e.g., DaTscan) aids diagnosis in atypical cases.

- Hoehn and Yahr Staging:

- Stage 1: Unilateral symptoms.

- Stage 2: Bilateral symptoms, no balance impairment.

- Stage 3: Balance impairment, mild to moderate disability.

- Stage 4: Severe disability; still able to walk/stand.

- Stage 5: Wheelchair/bed-bound.

- This image was taken from this blog post. It appears that a basic concern modern neurologists have with this scale is that it doesn’t account for motor and non-motor symptoms and doesn’t capture the functional status of the person. However, it is widely used across clinics and also used for billing purposes (or so I’ve seen).

Early Clues: Symptoms That May Appear Before Motor Issues in Parkinsonism

While diagnoses of Parkinson’s disease and similar conditions are often made based on motor symptoms—like tremors, stiffness, and slowness of movement—there are often non-motor symptoms that can show up years earlier. These early signs might not immediately point to Parkinson’s disease or parkinsonism but can be valuable clues for doctors. Here are some examples:

- REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD)

- Normally, during the REM stage of sleep (when dreams occur), the body is temporarily paralyzed to prevent acting out dreams. In people with RBD, this mechanism doesn’t work, leading to movements or vocalizations during sleep, such as kicking, punching, or shouting.

- RBD can precede the onset of Parkinson’s disease by years or even decades and is also linked to other parkinsonian disorders like multiple system atrophy (MSA) or dementia with Lewy bodies.

- Constipation

- Persistent constipation can be an early sign of Parkinson’s because the same loss of dopamine-producing neurons that affects movement can also impair the nerves that control the digestive system.

- This symptom may occur years before motor issues appear and is sometimes accompanied by other digestive problems, such as bloating or difficulty swallowing.

- Loss of Smell (Anosmia) A reduced or absent sense of smell is another common early symptom of Parkinson’s disease. Many people don’t notice this change right away or might not associate it with a neurological condition.

- Mood Changes Anxiety, depression, or apathy can appear early. These may result from changes in brain chemistry long before the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease become obvious.

- Fatigue and Sleep Issues People might experience excessive daytime sleepiness, trouble falling or staying asleep, or a general sense of fatigue. These symptoms may seem unrelated but can be part of the early changes caused by Parkinson’s.

- Subtle Changes in Movement Even before tremors or stiffness become noticeable, some people may have a slightly reduced arm swing when walking or minor difficulties with handwriting (micrographia).

What We Know

- PD diagnosis relies on clinical symptoms, primarily motor signs.

- Early diagnosis can improve quality of life with timely intervention.

What We Don’t Know

- How to reliably detect PD before symptoms appear.

- How non-motor symptoms relate to the progression of the disease.

Note!

Sometimes, people experience symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease, like shaking hands, slow movement, stiff muscles, or balance problems, but it doesn’t mean they have Parkinson’s disease. These symptoms are called “parkinsonism,” and they can happen for different reasons.

Here are some possible causes of parkinsonism that aren’t Parkinson’s disease:

-

Medications: Some drugs, like those used for mental health conditions (antipsychotics) or nausea, can cause temporary symptoms similar to Parkinson’s. This is called drug-induced parkinsonism, and it often improves if the medication is stopped or changed.

-

Other Neurological Conditions: Diseases like multiple system atrophy (MSA), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), or corticobasal degeneration (CBD) can also cause parkinsonian symptoms, but they have distinct features and progress differently.

-

Brain Injuries or Strokes: Damage to certain parts of the brain due to head trauma or a stroke can mimic Parkinson’s symptoms.

-

Toxins: Exposure to certain chemicals, like carbon monoxide or manganese, can lead to parkinsonism.

- Infections: Rare brain infections, such as encephalitis, can sometimes cause parkinsonian symptoms.

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH): This condition, caused by a buildup of fluid in the brain, can cause trouble walking, balance issues, and other symptoms that look like Parkinson’s.

5. Treatment Options

A. Pharmacological Treatments

Since we know that PD is linked to not being able to make dopamine, the treatment is part of the diagnosis itself. The treatment is just replacing the dopamine! If someone improves then this suggests that they have Parkinson’s (though diagnoses are only fully possible post-mortem!)

- Levodopa (L-DOPA):

- The gold standard for motor symptom relief.

- Often combined with Carbidopa (to prevent peripheral metabolism).

- Levodopa is the most effective treatment for Parkinson’s motor symptoms. It works by turning into dopamine in the brain, which helps replace the dopamine that’s missing.

- Carbidopa is often added to stop Levodopa from being broken down before it reaches the brain, ensuring more of it gets where it’s needed.

- Dopamine Agonists:

- E.g., Pramipexole, Ropinirole.

- Mimic dopamine’s effect on the brain.

- Drugs like Pramipexole and Ropinirole act like dopamine in the brain. They “trick” dopamine receptors into thinking they’re getting dopamine, which helps improve movement and reduce stiffness.

- These drugs can be used alone or with Levodopa.

- MAO-B Inhibitors:

- E.g., Selegiline, Rasagiline.

- Prevent dopamine breakdown.

- Examples include Selegiline and Rasagiline. These medications block an enzyme called MAO-B, which normally breaks down dopamine in the brain. By preventing this breakdown, the brain keeps more dopamine around for longer, which helps with movement.

- COMT Inhibitors:

- E.g., Entacapone.

- Extend Levodopa’s duration.

- Drugs like Entacapone help Levodopa work longer. They block another enzyme (COMT) that breaks down Levodopa before it turns into dopamine, ensuring it stays active for a longer time and reduces “off” periods when symptoms return.

- Anticholinergics: Useful for tremor in younger patients.

- These drugs, such as Benztropine, help control tremors, especially in younger patients. They work by blocking a chemical called acetylcholine, which helps balance the brain’s signaling systems when dopamine levels are low.

Note: we do not have anything right now that actually stops the disease as much as they are treating the symptoms of the disease.

How Dopamine Treatments Can Cause Further Issues: Dyskinesia and Beyond:

- In Parkinson’s disease, the brain loses cells that produce dopamine, a chemical critical for smooth and controlled movements. Medications like levodopa are often used to replace dopamine, which helps reduce the hallmark symptoms of Parkinson’s, such as tremors, stiffness, and slowness. However, while these treatments are highly effective, they can sometimes lead to further complications, including a movement disorder called dyskinesia.

What Is Dyskinesia?

- Dyskinesia refers to involuntary, erratic, and often excessive movements, such as twitching, writhing, or jerking motions. These movements can range from mild to severe and are different from the tremors typically seen in Parkinson’s disease.

Why Does Dyskinesia Happen?

-

Dyskinesia is thought to result from fluctuations in dopamine levels caused by the way Parkinson’s medications work:

- Levodopa Peaks and Troughs: Levodopa, the most common treatment, gets converted to dopamine in the brain. But its effects don’t last all day, leading to periods of high dopamine (peaks) and low dopamine (troughs). These fluctuations disrupt the brain’s ability to regulate movement.

- Long-Term Use: Over time, as Parkinson’s progresses, the brain’s ability to store and use dopamine efficiently decreases. This makes the effects of levodopa more erratic, increasing the likelihood of dyskinesia.

- Oversensitivity to Dopamine: The brain can become overly sensitive to dopamine, especially in areas responsible for movement. This heightened sensitivity can trigger involuntary movements.

- Note: sometimes you see the same effects with anti-psychotics

B. Non-Pharmacological Treatments

- Physical Therapy:

- Focus on balance, strength, and flexibility.

- Speech Therapy: Addresses hypophonia and swallowing issues.

- Occupational Therapy: Helps with daily activities.

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS):

- Surgical option for advanced cases unresponsive to medication.

What We Know

- Current treatments target symptoms but do not stop or reverse neurodegeneration.

- Combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies improves outcomes.

What We Don’t Know

- Why treatments work better for some patients than others.

- How to develop disease-modifying therapies that stop progression.

6. Current Research and Future Directions

Areas of Active Research:

- Pathogenesis: Investigating the role of alpha-synuclein, genetics, and environmental triggers.

- Biomarkers: Efforts to identify early diagnostic biomarkers (e.g., CSF alpha-synuclein).

- Neuroprotective Strategies: Trials focusing on slowing neurodegeneration.

- Gene Therapy: Potential to deliver neuroprotective proteins or enzymes.

- Stem Cell Research: Developing dopaminergic neurons for cell transplantation.

What We Know

- Genetic mutations (e.g., LRRK2, SNCA) are associated with PD in some patients.

- Environmental factors like pesticides may contribute to PD risk.

What We Don’t Know

- How gene-environment interactions trigger PD- see next section.

- How to translate promising animal model research into effective human therapies.

7. Risk Factors

- Why is the prevalence of PD increasing? A lot of the ideas in this section are discussed in the paper sent out: Dorsey & Bloem, 2024

- Better Diagnosis?: One common explanation for the rise in Parkinson’s disease (PD) is that increased awareness and improved diagnostic tools have led to higher detection rates over time. While this may hold some truth, it can only account for the relative increase in PD if these factors are more relevant to PD than to other neurological disorders like multiple sclerosis or stroke.

-

Increased aging?: PD rates have risen both in absolute numbers and when adjusted for age (GBD 2016 Parkinson’s Disease Collaborators, 2018). In contrast, while global Alzheimer’s disease prevalence more than doubled in absolute terms from 1990 to 2016, age-adjusted rates have remained relatively stable. This suggests that factors beyond aging alone are driving the rise in PD cases.

-

Sex?: Sociological rather than biological factors may contribute to sex differences in PD prevalence. For instance, in regions where men are more likely to be exposed to environmental toxicants like pesticides, PD is more common in men. Conversely, in areas where women are more frequently exposed to pesticides (e.g., through farming), PD is more prevalent among women (idea from Dorsey & Bloem, 2024). (Note for class: This is an example of correlation, not causation!)

- Exposure to toxins: Gene-environment relationships have been well-documented to play an important role. Several pesticides that have been linked to PD (e.g., paraquat, rotenone). These contaminants may extend to cleaning supplies, food, the stool of those ingesting them, water contamination, etc.

Air pollution, pesticides, and TCE (trichloroethylene) share several characteristics that may link them to Parkinson’s disease (PD):

- Mitochondrial Toxicity: These substances are toxic to mitochondria, which play a critical role in energy production, particularly in the brain—a highly energy-dependent organ. Dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, which are especially energy-demanding due to their extensive axon networks and synapses, are particularly vulnerable. Mitochondrial dysfunction is also central to genetic causes of PD (e.g., LRRK2, Parkin, SNCA), suggesting a shared mechanism that bridges genetic and environmental factors.

- Inhalation Pathways: These toxicants can enter the body through inhalation, bypassing protective barriers like the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and liver.They can reach the olfactory bulb directly, a region associated with early PD pathology and symptoms such as loss of smell (hyposmia), which is common in PD. This "nose-to-brain" pathway may explain how environmental exposures initiate early PD-related changes in the brain.

- Modern Environmental Origins: Large-scale air pollution, synthetic pesticides, and commercial TCE use are relatively recent phenomena, tied to industrialization and the post-World War II era. While natural toxins like rotenone have existed for centuries and may explain older cases of PD, the sharp global rise in PD aligns with increased exposure to modern environmental toxicants.

8. Summary and Key Takeaways

- Parkinson’s Disease is a progressive movement disorder caused by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons.

- Motor symptoms (TRAP) and non-motor symptoms impact patients’ quality of life.

- Treatment focuses on managing symptoms; no cure currently exists.

- Research is ongoing to uncover the disease’s pathogenesis, improve diagnosis, and find neuroprotective therapies.

9. Discussion Questions

- What are the limitations of current treatment options for PD?

- How might early detection of PD impact disease management and outcomes?

- Discuss what we know and don’t know about alpha-synuclein’s role in PD.

- What are the ethical implications of stem cell and gene therapy for PD?

- How might lifestyle and environmental changes reduce PD risk?

10. Future Work: Prognosis Across Groups

Understanding Variability in Progression

One of the key challenges in studying parkinsonian disorders is the variability in how symptoms progress among different groups of individuals. Future research should aim to:

- Identify and validate biomarkers that can predict disease progression across diverse patient populations.

- Investigate how genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors contribute to differences in prognosis.

Stratification by Subtypes

Parkinsonian disorders encompass a wide range of subtypes, including idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, atypical parkinsonism, and secondary parkinsonism. Future studies should:

- Focus on refining diagnostic criteria to differentiate subtypes more effectively.

- Explore whether specific subtypes exhibit unique progression patterns or treatment responses.

Subtypes:

- Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

- Definition: Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease is the most common form of parkinsonism and is considered a neurodegenerative disorder. The term “idiopathic” means that the exact cause is unknown. It is primarily characterized by the gradual loss of dopamine-producing neurons in a region of the brain called the substantia nigra.

- Key Features:

- Symptoms include tremors, bradykinesia (slowness of movement), rigidity, and postural instability.

- Non-motor symptoms, such as depression, constipation, and sleep disturbances, are also common.

- It typically responds well to dopamine replacement therapy (e.g., levodopa).

- Cause: While the exact cause is unknown, genetic and environmental factors may contribute.

- Atypical Parkinsonism

- Definition: Atypical parkinsonism refers to a group of disorders that share some features of Parkinson’s disease, such as tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia, but have distinct underlying causes and often do not respond as well to dopamine replacement therapy.

- Examples:

- Multiple System Atrophy (MSA): A rare condition involving widespread damage to the autonomic nervous system and motor control centers.

- Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP): Characterized by difficulties with balance, eye movements, and speech.

- Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD): Marked by asymmetric motor dysfunction and cognitive decline.

- Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB): Combines parkinsonian motor symptoms with significant cognitive impairment and hallucinations.

- Key Differences from PD:

- Symptoms tend to progress more rapidly.

- Poor response to levodopa.

- Additional features such as early autonomic dysfunction, severe balance issues, or cognitive decline are often present.

- Secondary Parkinsonism

- Definition: Secondary parkinsonism refers to parkinsonian symptoms caused by an identifiable, external cause rather than a neurodegenerative process.

- Common Causes:

- Medication-Induced: Certain drugs, especially antipsychotics and anti-nausea medications, can block dopamine receptors and mimic Parkinson’s symptoms.

- Vascular Parkinsonism: Caused by multiple small strokes affecting brain areas involved in movement.

- Toxins: Exposure to substances like carbon monoxide or manganese.

- Brain Trauma: Repeated head injuries (as seen in some athletes) can lead to parkinsonism.

- Infections: Rare cases of brain infections, such as post-encephalitic parkinsonism.

- Key Features:

- Symptoms depend on the underlying cause but often include tremors, rigidity, and slowed movement.

- Treating the underlying cause (e.g., stopping the offending medication) can improve or resolve symptoms in some cases.

Prognostic Tools and Models

Developing tools to predict individual outcomes could significantly improve patient care and resource allocation. Efforts should be directed toward:

- Creating machine learning models that integrate clinical, genetic, and imaging data to provide personalized prognoses.

- Validating these models in real-world clinical settings to ensure reliability and applicability.

Longitudinal Studies

Current research is often limited by short study durations or small sample sizes. To overcome these limitations:

- Long-term, large-scale cohort studies should be conducted to monitor disease trajectories over time.

- Efforts should include underrepresented populations to ensure findings are generalizable.

Integration of Multidisciplinary Approaches

Progress in prognosis research will likely benefit from collaboration across disciplines. This includes:

- Neurology, for clinical insights and patient management.

- Data science, for the development of predictive algorithms.

- Epidemiology, for understanding population-level trends.

Implications for Treatment and Care

Improved prognostic tools and knowledge can lead to:

- Earlier interventions tailored to individual risk profiles.

- Better planning for long-term care needs, including managing potential complications.

In summary, future research on prognosis across groups should aim to bridge gaps in knowledge, improve predictive accuracy, and ultimately enhance outcomes for patients with parkinsonian disorders.

Interesting facts:

- Evolutionarily, humans have a lot less dopamine neurons than rodents!

References

- Books:

- Kandel, E. R., Schwartz, J. H., & Jessell, T. M. (2000). Principles of Neural Science.

- Articles:

- Lees, A. J., Hardy, J., & Revesz, T. (2009). Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet, 373(9680), 2055–2066.

- Cramb, K.M.L., Beccano-Kelly, D., Cragg, S.J., Wade-Martins, R., Impaired dopamine release in Parkinson’s disease, Brain, Volume 146, Issue 8, August 2023, Pages 3117–3132, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awad064 (pdf on Class Drive)

- Dorsey, E. R., & Bloem, B. R. (2024). Parkinson’s Disease Is Predominantly an Environmental Disease. Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. https://doi.org/10.3233_JPD-230357 (pdf on Class Drive)

- Relevant Websites:

- Parkinson’s Foundation: www.parkinson.org

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke: www.ninds.nih.gov