Lecture- Understanding Depression

Objectives

By the end of this lecture, the goal is to be able to:

- Understand the basic biology of mood regulation and neurotransmitters.

- Define depression and describe its epidemiology.

- Discuss the neurobiology and pathology of depression.

- Identify the clinical symptoms, diagnosis, and risk factors for depression.

- Explore treatment options, including pharmacological and psychotherapeutic approaches.

- Discuss what we know and what remains unknown about depression.

- Examine current research trends and future directions for depression treatment.

1. Basic Biology of Mood Regulation

- Brain Regions Involved:

- Neurotransmitters:

- Serotonin: Regulates mood, appetite, and sleep.

- Norepinephrine: Involved in energy, focus, and arousal.

- Dopamine: Associated with reward, pleasure, and motivation.

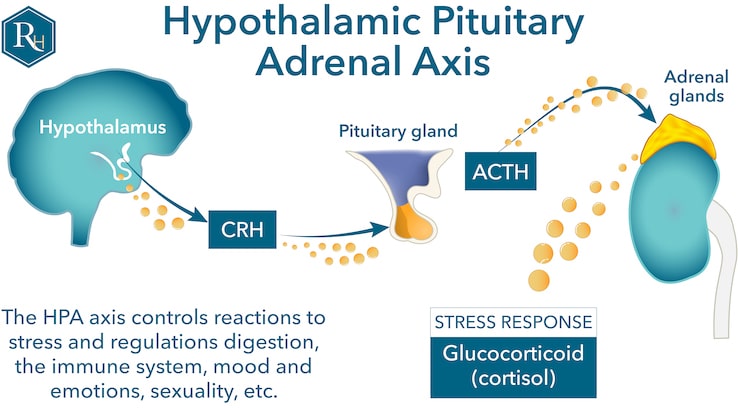

- HPA Axis Dysfunction:

2. Introduction to Depression

- Definition:

- Depression (Major Depressive Disorder, MDD) is a common and debilitating mood disorder characterized by persistent sadness, loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities, and impaired daily functioning.

- It encompasses emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and physical symptoms that vary in severity and duration.

- Just because you are depressed, it does not mean you have MDD

- Though we use the term “depression” colloquially often, MDD is distinct from other types of depression such as

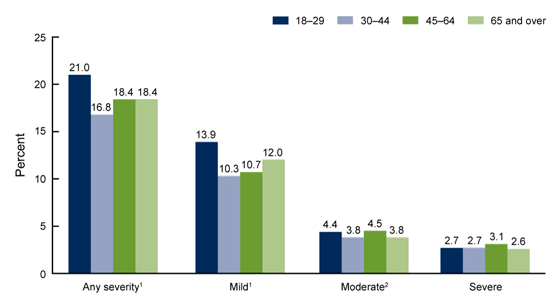

- Epidemiology:

- Affects approximately 7% of adults (18+) annually worldwide, with prevalence rates differing across regions and demographics.

- Around 8.4% of U.S. adults had MDD in 2020, but in adolescence it jumps to 17%.

- Around 20% of people in the United States will experience a depressive episode at least once in their life.

- Depression is the number one cause of disability in the whole world (6% of the U.S. population in 2020).

- Women are nearly twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with depression, potentially due to hormonal, psychosocial, and cultural factors. During adolescence rates are even higher, but arguments could be made that men may be misdiagnosed.

- Onset is often in late adolescence or early adulthood, though it can occur at any age.

- Chart from the CDC

- Impact:

- A leading cause of disability globally, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO).

3. Neurobiology and Pathology of Depression

Some probable causes for depression:

- Genetics

- If parents have depression, you are more likely to experience genetics

- This is often studied using twin studies where the genes are identical, but the environments may not be.

- Monoamine Hypothesis:

- Depression has been historically linked to deficits in monoamines—serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine—which regulate mood, reward, and stress responses.

- While this hypothesis has driven drug development, it does not fully explain all cases, highlighting the complexity of depression’s etiology.

The Monoamine Hypothesis is one of the earliest and most widely discussed theories about the biological basis of depression. It posits that the condition arises from a deficiency in specific neurotransmitters—serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine—known collectively as monoamines. These neurotransmitters play critical roles in regulating mood, reward, and stress responses:

- Serotonin: Often referred to as the “feel-good” neurotransmitter, serotonin helps regulate mood, appetite, sleep, and emotional well-being. A deficiency in serotonin has been linked to symptoms such as persistent sadness, irritability, and sleep disturbances.

- Dopamine: Central to the brain’s reward and motivation systems, dopamine deficits can contribute to anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure), low motivation, and fatigue.

- Norepinephrine: Important for alertness and arousal, norepinephrine deficiencies may result in lack of energy, concentration difficulties, and a general sense of apathy.

Impact on Drug Development

The monoamine hypothesis heavily influenced the development of antidepressant medications. Drugs such as Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g., fluoxetine, sertraline) and Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) (e.g., venlafaxine, duloxetine) were designed to increase the availability of these neurotransmitters in the brain. These medications work by blocking the reuptake of serotonin and/or norepinephrine into presynaptic neurons, allowing more of these chemicals to remain active in the synaptic cleft.

Limitations and Complexity

While the monoamine hypothesis provides a useful framework, it does not fully explain the complexity of depression. Key limitations include:

-

Delayed Onset of Antidepressant Effects: Although SSRIs and similar medications increase neurotransmitter levels almost immediately, patients often take weeks to experience symptom relief. This suggests that the mechanism of action involves downstream changes, such as neuroplasticity, rather than just correcting neurotransmitter levels.

-

Non-Responsiveness in Some Patients: A significant proportion of individuals with depression (30–40%) do not respond to first-line antidepressants, indicating that other factors beyond monoamine deficits contribute to the condition.

- Broader Neurobiological Factors: Emerging research highlights the involvement of:

- Neuroinflammation: Elevated levels of inflammatory markers like cytokines in some individuals with depression.

- HPA Axis Dysregulation: Chronic stress and dysregulated cortisol levels impacting brain structure and function.

- Neuroplasticity: Impaired ability of the brain to adapt and form new connections, particularly in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

- Heterogeneity of Depression: Depression is not a single disorder but a heterogeneous condition with multiple subtypes and contributing factors, including genetics, environment, and psychosocial stressors. The monoamine hypothesis cannot account for all these variations.

Current Perspectives

Modern research considers the monoamine hypothesis as one piece of the puzzle. While it has provided valuable insights and guided effective treatments for many patients, the etiology of depression is now understood to involve a complex interplay of genetic, neurobiological, environmental, and psychological factors. This broader understanding is driving the exploration of novel treatments, such as ketamine, psychedelics, and personalized medicine approaches that go beyond the monoamine framework. It also suggests that other hypotheses need to be investigated.

- HPA Axis Dysregulation:

- Chronic stress and hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis can lead to elevated cortisol levels, which have neurotoxic effects on brain regions like the hippocampus.

- Brain Changes:

- Structural:

- Decreased hippocampal volume linked to memory deficits and emotional regulation challenges.

- Reduced prefrontal cortex volume associated with impaired executive function.

- Functional:

- Hyperactivity in the amygdala contributes to heightened emotional reactivity.

- Major depressive disorder (MDD) has been linked to imbalanced communication among large-scale brain networks

- Reduced connectivity in the default mode network (DMN) may impair self-referential processing.

- Network Level Discussions:

- Network-level theories of depression focus on the dysfunction of brain networks involved in emotion regulation, reward processing, and self-referential thinking. Key networks implicated in depression include:

- Default Mode Network (DMN): Overactivity in the DMN, particularly during rest, is linked to excessive rumination and self-focused negative thoughts, common in depression.

- Ventral attention (Salience) Network (SN): Impaired functioning of the SN, which helps detect and prioritize emotionally significant stimuli, can result in difficulty processing and responding to emotional cues.

- Central Executive Network (CEN): Underactivity in the CEN is associated with cognitive impairments, such as poor concentration and decision-making difficulties, often seen in depression.

- Simplically, these network-level disruptions result in an imbalance between introspection (DMN activity) and attention to external stimuli (SN and CEN activity). Treatments such as antidepressants, psychotherapy, and non-invasive brain stimulation aim to restore balance between these networks. Emerging approaches like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and psychedelic-assisted therapy show promise in modulating network connectivity and promoting functional recovery in depression.

- There is a lot more to be investigated in this space.

- Structural:

- Neuroinflammation:

- Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in some individuals suggest an immune component to depression.

- It is worth nothing that having low-inflammatory diets has been shown to correlate with lower rates of MDD.

- Loneliness

- Studies show that socialization can improve depressive symptoms

- There is a sense that when we are connected with other people, it makes things easier when we are going through a hard time (misery loves company)

- A great discussion of loneliness can be found here: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/05/ce-corner-isolation

4. Clinical Symptoms and Diagnosis

- Core Symptoms:

- Persistent sadness or low mood most of the day, nearly every day.

- Anhedonia (loss of interest or pleasure in most activities).

- Fatigue or low energy, even with adequate rest.

- Difficulties in concentrating, making decisions, or remembering details.

- Changes in sleep patterns (insomnia or hypersomnia) and appetite (increased or decreased).

- Other Symptoms:

- Feelings of worthlessness, excessive guilt, or self-blame.

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation (observable by others).

- Suicidal ideation, with or without specific plans.

- Diagnosis:

- Based on DSM-5 criteria: presence of at least five symptoms for a minimum of two weeks (“episode”), causing significant distress or impairment. It cannot be something that you feel for the short-term.

- The 9 criteria from the DSM-5 are:

- Feeling empty or hopeless for most of the day

- Having little interest or pleasure in doing things that you normally enjoy (anhedonia)

- Need to have one of the two above to have MDD

- Changes in sleep (insomnia or hypersomnia)

- Feeling fatigued or having decreased energy levels relative to baseline

- Changing in your normal appetite or eating patterns relative to normal

- Feeling of excessive guilt or worthlessness

- Decreased ability to concentrate or being abnormally indecisive (could it be driven by intrusive negative thoughts)

- Sense of restlessness (“cannot sit still”; psychomotor agitation) or sense of inability to be active (psychomotor retardation)

- The same individual can have both!

- Suicidal thoughts

- Other symptoms that are often part of the clinical picture:

- emotional numbness

- apathy

- irritability

- anger outbursts (especially common in men during adolescence)

- discussion of cultural norms

- crying spells

- loss of libido

- self-harm

- Exclusion of other medical or substance-induced causes.

5. Treatment and Management

-

There is not one size fits all approach

-

Pharmacotherapy:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are first-line treatments.

- see purple inset above on more information

- A video on how SSRIs work:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are first-line treatments.

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are older classes, used less frequently due to side effects.

-

Newer treatments include atypical antidepressants like bupropion and mirtazapine.

- Psychotherapy:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Focuses on identifying and modifying negative thought patterns and behaviors.

- “aha” moments

- Behavioral Activation (BA): Encourages engagement in activities to counteract anhedonia and improve mood.

- Interpersonal Therapy (IPT): Addresses interpersonal issues contributing to depressive symptoms.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Focuses on identifying and modifying negative thought patterns and behaviors.

- Lifestyle Interventions:

- Regular physical activity, a balanced diet, and sufficient sleep are crucial adjuncts to treatment.

- Mindfulness-based practices and stress management techniques may also benefit individuals with depression.

- Emerging Treatments:

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been shown to have a significant and relatively immediate effect

- There are major concerns when it comes to side-effects such as memory loss or it can be a traumatic experience for some.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) as a non-invasive option. Link on more information from the Mayo Clinic.

- Typically used for medication resistant depression.

How Does TMS Work?

- Magnetic Pulses: During a TMS session, a special device delivers magnetic pulses to your brain. These pulses are painless and feel like gentle tapping on your head.

- Targeting Brain Areas: The magnetic pulses are directed at a specific part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in mood regulation. In people with depression, this area may be underactive. TMS helps “wake it up” and restore normal activity. There are also claims that this improves communication by stimulating the connections between different regions of the brain. This improved communication can reduce symptoms of depression.

- A common protocol is to stimulate the left frontal lobe (which has been shown to be underactive). This is distinct from the medications that often work at a chemical level, while this is working at the level of electrical impulses.

- An interesting recent paper on TMS (and accelerating it!): Gogulski et al., (2022) Personalized Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Depression Link

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been shown to have a significant and relatively immediate effect

6. Current Research and Future Directions

- Novel Pharmacological Agents:

- Ketamine and esketamine are showing promise as rapid-acting antidepressants, particularly for treatment-resistant depression.

- Psychedelics like psilocybin are under investigation for their potential to promote neuroplasticity and lasting mood improvements.

How Psychedelic Drugs May Help with Depression

- Psychedelic drugs such as psilocybin and MDMA show potential for treating treatment-resistant depression and post-traumatic stress disorder by promoting neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to form new connections between neurons. These drugs activate receptors inside brain cells called 5-HT2A receptors, which are crucial for this process.

- A study revealed that compounds capable of crossing a neuron’s membrane and binding to intracellular 5-HT2A receptors are more effective at stimulating the growth of dendritic spines (connections between neurons) than those binding only to surface receptors. This finding explains why serotonin, despite binding to 5-HT2A receptors, does not promote neuroplasticity as these psychedelics do.

- In mouse models, facilitating serotonin’s entry into neurons enhanced dendritic spine growth and showed improvements in behaviors linked to depression. These insights suggest new possibilities for designing drugs that stimulate brain plasticity without causing hallucinogenic effects, paving the way for safer, targeted treatments for depression.

- Further research is needed to refine these approaches and better understand how to activate brain plasticity mechanisms effectively.

- Study: Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Vargas MV, Dunlap LE, Dong C, Carter SJ, Tombari RJ, Jami SA, Cameron LP, Patel SD, Hennessey JJ, Saeger HN, McCorvy JD, Gray JA, Tian L, Olson DE. Science. 2023 Feb 17;379(6633):700-706. doi: 10.1126/science.adf0435. Epub 2023 Feb 16. PMID: 36795823.

- Lay scientific summary: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/how-psychedelic-drugs-may-help-depression

- Personalized Medicine:

- Advances in genetics and neuroimaging may allow for tailored treatments based on individual biomarkers.

- Neurocircuitry and Brain Stimulation:

- Deep brain stimulation (DBS) targeting specific regions such as the subgenual cingulate cortex.

- Digital Health:

- Mobile apps and teletherapy platforms are improving accessibility and adherence to treatments.

7. Summary

Depression is a complex and multifactorial disorder that significantly impacts individuals and society. Advances in our understanding of its neurobiology and the development of innovative treatments hold promise for improving outcomes. Early diagnosis and a holistic approach to care remain pivotal in managing this condition.

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) vs. Other Types of Depression

Depression is a complex mental health condition that manifests in various forms. While Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is one of the most commonly diagnosed types, there are other forms of depression with unique characteristics. Below is a comparison between MDD and other types of depression:

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

- Definition: MDD, also known as clinical depression, is a mood disorder characterized by persistent and intense feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a loss of interest in activities.

- Duration: Symptoms typically last for at least two weeks or longer.

- Key Symptoms:

- Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day.

- Loss of interest or pleasure in most activities.

- Significant changes in weight or appetite.

- Sleep disturbances (insomnia or hypersomnia).

- Fatigue or loss of energy.

- Difficulty concentrating or making decisions.

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt.

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide.

- Diagnosis Criteria: Requires the presence of five or more symptoms for at least two weeks, significantly impairing daily functioning.

Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD)

- Definition: Also called dysthymia, PDD is a chronic form of depression with less severe but longer-lasting symptoms than MDD.

- Duration: Symptoms persist for at least two years in adults.

- Key Differences from MDD:

- Symptoms are less intense but more persistent.

- Individuals may experience periods of normal mood that last less than two months.

Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD)

- Definition: A type of depression linked to changes in seasons, often occurring during fall and winter.

- Duration: Symptoms typically resolve with the arrival of spring or summer.

- Key Features:

- Related to reduced exposure to sunlight.

- May include fatigue, weight gain, and social withdrawal.

Bipolar Disorder (Depressive Episodes)

- Definition: Bipolar disorder includes depressive episodes similar to MDD but alternates with periods of mania or hypomania.

- Key Differences from MDD:

- Episodes of elevated mood, energy, and activity (mania or hypomania) distinguish bipolar disorder from MDD.

- Treatment often involves mood stabilizers in addition to antidepressants.

Postpartum Depression (PPD)

- Definition: A type of depression that occurs after childbirth.

- Key Features:

- Includes feelings of sadness, anxiety, and exhaustion that interfere with caregiving.

- Hormonal changes and life stressors contribute to its onset.

Psychotic Depression

- Definition: A severe form of depression accompanied by psychosis, such as delusions or hallucinations.

- Key Features:

- Psychotic symptoms are congruent with depressive themes (e.g., guilt, worthlessness).

- Requires specialized treatment, often combining antidepressants and antipsychotics.

Atypical Depression

- Definition: A subtype of depression with specific features, such as mood reactivity.

- Key Features:

- Individuals may experience improved mood in response to positive events.

- Other symptoms include increased appetite, excessive sleep, and heaviness in limbs.

Understanding the differences between MDD and other types of depression is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Discussion Questions

- How might emerging treatments like ketamine reshape the management of depression?

- What are the implications of neuroinflammation in understanding and treating depression?

- How can digital health tools be leveraged to improve accessibility and adherence to therapy?

- What challenges exist in bridging the gap between research advancements and clinical practice for depression?

References

Scheepens, D. S., Van Waarde, J. A., Lok, A., De Vries, G., Denys, D. A., & Van Wingen, G. A. (2020). The Link Between Structural and Functional Brain Abnormalities in Depression: A Systematic Review of Multimodal Neuroimaging Studies. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 486702. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00485

An extensive (10 min) video on depression: