Lecture- Understanding Alzheimer's Disease

"All Models Are Wrong, Some Are Useful" - George Box

Or, that's what Karl Herrup in his book "How Not to Study a Disease" would say

Image from: https://vajiramandravi.com/upsc-daily-current-affairs/prelims-pointers/alzheimer%27s-disease/ Hover for more information

Objectives

By the end of this lecture, students should be able to:

- Understand the basic biology of memory and brain function.

- Define Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and understand its epidemiology.

- Describe the neurobiology and pathology of AD.

- Discuss the clinical symptoms, stages, and diagnosis of the disease.

- Explore current treatment options and management strategies.

- Discuss what we know and what remains unknown about AD.

- Examine ongoing research and future directions in AD treatment.

1. Basic Biology of Memory and Brain Function

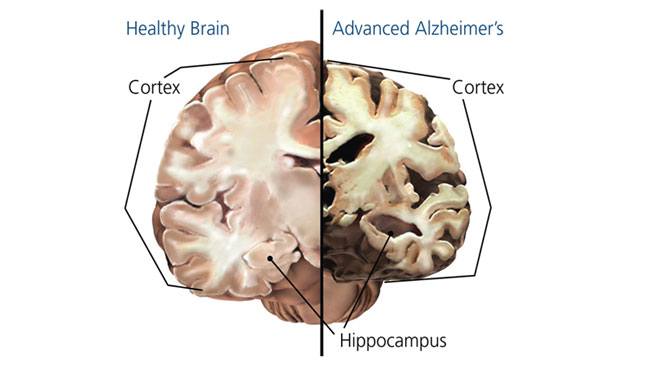

- The Role of the Hippocampus:

- The hippocampus is a key brain region involved in memory formation and spatial navigation.

- Damage to the hippocampus is one of the earliest changes seen in AD.

- Neural Communication:

- Neurons communicate via synapses, where neurotransmitters like acetylcholine are released.

- Acetylcholine is critical for memory, attention, and learning.

- Brain Plasticity:

- The brain’s ability to form new connections is essential for learning and recovery.

- AD disrupts plasticity and causes widespread neuronal death.

- Neurodegeneration:

- Loss of synapses and neurons impairs cognitive functions and leads to brain atrophy.

2. Introduction to Alzheimer’s Disease

- Definition:

- Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects memory and cognition.

- History:

- First described by Dr. Alois Alzheimer in 1906.

- Epidemiology:

- Most common cause of dementia (~60-70% of cases).

- Affects ~10% of people over 65, with prevalence doubling every 5 years after 65.

- Higher prevalence in females (likely due to longevity).

- Useful summary video:

What We Know

- AD is the leading cause of dementia worldwide.

- Risk increases significantly with age.

- Engagement in frequent navigational and spatial processing tasks, as performed by taxi and ambulance drivers, might be associated with some protection against Alzheimer’s disease (recent paper: Patel et al. 2024)

What We Don’t Know

- Why women are disproportionately affected beyond aging.

- Whether lifestyle, genetics, or environment plays a dominant role in disease onset.

3. Neurobiology and Pathology of AD

- Key Brain Changes:

- Atrophy of the hippocampus and cortex.

- Loss of synapses and neurons in critical brain regions.

- Pathological Hallmarks:

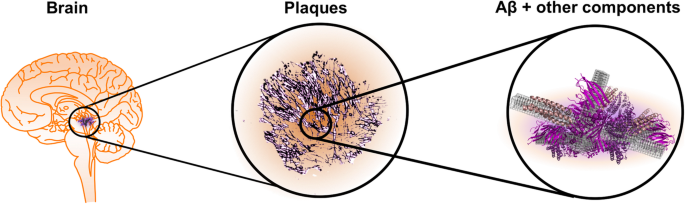

What doctors look for in the brain to “diagnose” AD:- Amyloid Plaques:

- These are clumps of a sticky protein (“extracellular deposits”) called beta-amyloid (Aβ) that build up between brain cells.

- These plaques may block communication between cells and trigger inflammation, leading to damage.

- Neurofibrillary Tangles (NFTs):

- Inside the brain cells, another protein called tau gets twisted into tangles. Tau normally has a lot of important functions including supporting microtubules and maintaining the metabolism of glucose.

- These tangles mess up the cell’s transport system (microtubules), preventing nutrients and other materials from moving properly, which causes the cell to die.

- Pathological tau not only disrupts microtubule stability, but also instigates an immune response (see below)

Image from Rahman, M.M., Lendel, C. Extracellular protein components of amyloid plaques and their roles in Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Mol Neurodegeneration 16, 59 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-021-00465-0. Hover for more information

- Amyloid Plaques:

- The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis:

- Scientists believe that the build-up of beta-amyloid sets off a chain reaction (a “cascade”).

- This cascade damages brain cells and leads to tangles, inflammation, and eventually, the widespread brain cell death seen in Alzheimer’s.

- This is the prominent hypothesis that is being tested and funded (proposed by Hardy and Higgins (1992))

- Inflammation and Neurodegeneration:

- Besides Aβ plaques and intracellular NFTs, neuroinflammation has been identified as the third core feature in AD pathogenesis

- The brain’s immune cells (glial cells) try to help by cleaning up damage but can overreact, causing inflammation that makes things worse.

- Oxidative stress, caused by harmful molecules, adds to the damage, further harming neurons and their ability to communicate.

- A recent article from last year offers a review of the inflammatory aspects of AD.

What We Know

- Beta-amyloid and tau protein abnormalities are key hallmarks of AD.

- Neurodegeneration begins decades before clinical symptoms appear.

What We Don’t Know

- Is beta-amyloid accumulation a cause or consequence of the disease?

- Why some individuals with plaques/tangles do not develop cognitive symptoms.

- Correlation is not causation

- About 30% of people have plaques, but no behaviors!

- Plaques are seen in other non-AD disorders such as Parkinson’s, epilepsy, Huntington’s

Image from: https://www.sfn.org/sitecore/content/home/brainfacts2/archives/2012/alzheimers-disease-today Hover for more information

Understanding the Genetic Basis of Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is influenced by a combination of genetics, lifestyle, and environmental factors. While most cases are not purely inherited, genetics plays a key role in determining a person’s risk of developing the disease. Here’s a simple breakdown:

Two Types of Alzheimer’s:

- Early-Onset Alzheimer’s (Rare):

- Happens before the age of 65, often due to inherited genetic mutations.

- Caused by mutations in specific genes, such as APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2. These mutations lead to abnormal processing of a protein called beta-amyloid, which builds up into plaques in the brain—a hallmark of Alzheimer’s.

- If you inherit one of these mutations, the chance of developing Alzheimer’s is almost 100%.

- Late-Onset Alzheimer’s (Common):

- Happens after the age of 65 and has a more complex genetic background.

- The most well-known genetic risk factor is the APOE gene, especially the APOE-e4 variant.

- If you inherit one copy of APOE-e4, your risk increases.

- If you inherit two copies (one from each parent), the risk is even higher.

- However, having APOE-e4 does not guarantee you’ll develop Alzheimer’s, and many people without this gene still get the disease.

How Do These Genes Affect the Brain?

- APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 Genes:

- These genes are involved in producing and processing amyloid precursor protein (APP), which gets broken down into beta-amyloid. Mutations can cause beta-amyloid to build up, forming plaques that damage brain cells.

- APOE-e4 Gene:

- This gene affects how the brain handles cholesterol and repairs itself. APOE-e4 makes it harder for the brain to clear beta-amyloid, leading to plaque build-up and inflammation, both of which harm brain cells.

Is Alzheimer’s Inherited?

- Early-Onset Alzheimer’s: Strongly inherited. If a parent has a gene mutation like PSEN1, you have a 50% chance of inheriting it.

- Late-Onset Alzheimer’s: More about risk than certainty. Even if you inherit APOE-e4, lifestyle factors like exercise, diet, and managing chronic conditions can reduce your risk.

4. Clinical Symptoms and Stages

- Early Symptoms:

- Memory loss (especially short-term memory).

- Difficulty finding words or remembering names.

- Progression of Symptoms:

- Impaired problem-solving and decision-making.

- Difficulty performing daily tasks.

- Behavioral changes (e.g., agitation, aggression).

- Late-stage: Severe memory loss, loss of motor function, inability to communicate.

- Note: given how difficult it has been to characterize the biological underpinnings so may argue it is better to focus on behavioral symptoms in diagnoses

Stages of AD:

- Preclinical Stage:

- No outward symptoms, but amyloid plaques and tau tangles may be present.

- Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI):

- Noticeable cognitive decline without significant daily interference.

- Alzheimer’s Dementia:

- Progressive decline in memory, cognition, and independence.

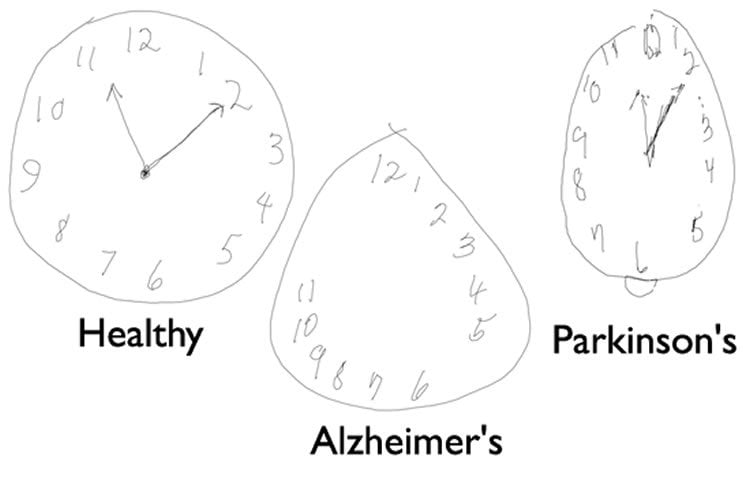

Diagnosis:

- Clinical evaluation and cognitive testing (e.g., MMSE, MoCA).

- Cognitive Tests: Tools like the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) are used to assess memory, attention, language, and problem-solving skills.

- The MMSE includes tasks like recalling a list of words or drawing a clock, which help identify areas of cognitive decline. The MoCA is often used for more sensitive detection of mild cognitive impairment.

- Imaging: MRI (atrophy), PET (amyloid/tau visualization).

- Biomarkers: CSF beta-amyloid, tau proteins.

- Blood Biomarkers (Emerging): New tests are being developed to detect Alzheimer’s-related changes in blood, offering a less invasive alternative to CSF testing.

More on blood biomarkers

- This article was distributed:

- Schöll, Michael et al. Challenges in the practical implementation of blood biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Healthy Longevity, Volume 5, Issue 10, 100630

Blood Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease

Blood biomarkers are becoming a promising way to detect Alzheimer’s disease earlier and more easily. These tests analyze proteins or molecules in the blood that are linked to brain changes seen in Alzheimer’s. Here’s how they work:

Types of Blood Biomarkers

- Markers for Alzheimer’s Hallmarks:

- These include proteins linked to amyloid plaques (e.g., beta-amyloid ratios) and tau tangles (e.g., phosphorylated tau or p-tau).

- Tau levels in the blood are particularly accurate at identifying Alzheimer’s and predicting positive results on specialized brain scans or spinal fluid tests.

- Markers of Neuron Damage:

- These biomarkers show signs of brain cell loss or damage, which happens as Alzheimer’s progresses. For example, neurofilament light chain (NfL) can signal damage to neurons.

- Markers of Brain Inflammation:

- Proteins like GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) indicate inflammation caused by the brain’s immune response, which is common in Alzheimer’s.

Why Blood Biomarkers Are Exciting

- Easier Testing: Unlike traditional methods like spinal taps or PET scans, blood tests are less invasive and could one day be done at a regular doctor’s office.

- Cost-Effective: Blood biomarkers are cheaper than many current diagnostic tools, potentially cutting costs by up to 40%.

- Faster Results: These tests can speed up diagnosis and reduce the time needed for additional testing.

Challenges to Widespread Use

- Standardization: Different labs and test methods can produce slightly different results, so scientists are working to make these tests reliable everywhere.

- Access: Advanced testing methods, like mass spectrometry, are not yet widely available in all regions or labs. Efforts are being made to simplify these tests for broader use.

- Confounding Factors: Conditions like kidney disease or heart problems can affect biomarker levels, making it harder to interpret results. Researchers are developing ways to adjust for these influences.

What’s Next?

- Blood biomarker testing is improving quickly, and newer methods like dried blood spot collection (using just a finger prick) may make testing available even in remote or underserved areas.

- Combining blood biomarkers with simple cognitive tests could make Alzheimer’s diagnosis faster, cheaper, and more accurate in the future.

These tests are not yet perfect but hold great promise for detecting Alzheimer’s disease earlier, guiding treatment, and making diagnostics more accessible to everyone.

What We Know

- AD progresses slowly over several years.

- Biomarkers can help identify the disease before clinical symptoms arise.

What We Don’t Know

- How to predict which individuals with MCI will progress to AD.

- Why progression varies significantly between individuals.

5. Treatment and Management

A. Pharmacological Treatments

- Current Medications (symptomatic relief):

- Cholinesterase Inhibitors (e.g., Donepezil, Rivastigmine):

- Increase acetylcholine levels to improve cognition.

- NMDA Receptor Antagonist (e.g., Memantine):

- Reduces glutamate toxicity.

- Cholinesterase Inhibitors (e.g., Donepezil, Rivastigmine):

B. Non-Pharmacological Interventions

- Cognitive Stimulation: Activities to maintain memory and mental function.

- Physical Activity: Exercise slows cognitive decline.

- Diet: Mediterranean diet shows potential benefits.

- Recent paper: Shannon, O.M., Ranson, J.M., Gregory, S. et al. Mediterranean diet adherence is associated with lower dementia risk, independent of genetic predisposition: findings from the UK Biobank prospective cohort study. BMC Med 21, 81 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02772-3

- Social Engagement: Reduces isolation and supports mental health.

What We Know

- Current treatments manage symptoms but do not halt disease progression.

- Lifestyle modifications (e.g., exercise, diet) may slow cognitive decline.

What We Don’t Know

- How to develop effective disease-modifying treatments.

- Why treatments work differently in individuals.

6. Current Research and Future Directions

- Early Detection:

- Development of more sensitive biomarkers for preclinical diagnosis.

- Disease-Modifying Therapies:

- Anti-amyloid therapies (e.g., monoclonal antibodies like Aducanumab).

- Anti-tau therapies to prevent tangle formation.

- lecanemab: an anti-amyloid antibody given intravenously, did show an effect on cognitive measures and is now an approved drug

- Lifestyle and Prevention:

- Studying the role of exercise, sleep, and diet in delaying onset.

- Genetics and Precision Medicine:

- Understanding APOE-e4 (a major genetic risk factor).

- Exploring personalized approaches to treatment.

What We Know

- Research has identified promising therapeutic targets like beta-amyloid and tau.

- Lifestyle interventions show potential in reducing risk.

What We Don’t Know

- Whether removing plaques or tangles improves cognition long-term.

- How genetic and environmental factors interact to trigger AD.

7. Summary and Key Takeaways

- Alzheimer’s Disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia.

- Pathological hallmarks include beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles, leading to neurodegeneration.

- Current treatments provide symptomatic relief but do not alter disease progression.

- Research efforts focus on early detection, disease-modifying therapies, and prevention strategies.

8. Discussion Questions

- What are the limitations of current treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease?

- How could early detection of AD change its management and outcomes?

- Discuss the role of genetics (e.g., APOE-e4) in AD. Is it deterministic or probabilistic?

- Why is the amyloid hypothesis controversial, and what are the alternatives?

- What lifestyle factors might help reduce the risk of developing AD?

References

- Books:

- Herrup, K. (2021). How Not to Study a Disease: The Story of Alzheimer’s. MIT Press.

- Articles:

- Jack, C. R., et al. (2018). NIA-AA Research Framework for AD. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(4), 535-562.

- Patel, et al. (2024) Alzheimer’s disease mortality among taxi and ambulance drivers: population based cross sectional study. Link

- Websites:

- Alzheimer’s Association: www.alz.org

- National Institute on Aging: www.nia.nih.gov